LIAONING, Northeast China — The best season to harvest sea cucumbers along the coast of the Yellow and Bohai seas is when fall turns to winter and the waters become icy cold.

Grasping hold of the boat as he surfaces, 40-year-old Wang Zhonghua puts one foot on the deck and pulls himself on board. Untying his oxygen tank and the heavy lead weights he uses to walk along the sea floor, he breathes a long sigh of relief. It’s hard work.

At 6 in the morning, Wang and three of his colleagues had set out from their homes on the Changshan Islands, near the coastal city of Dalian. Every day during the harvest season, they dive 20 to 30 meters beneath the waves and scour the muddy seabed for sea cucumbers — creatures that look like small, gray mangoes with little horns on their skin.

The marine animal is a crucial part of northern Chinese cuisine. It is most often sold dried, and can cost more than 7,000 yuan (over $1,000) per kilogram. In Dalian, custom dictates that people eat sea cucumbers for 81 days straight when winter starts; some people stew the animals and eat them for breakfast with rice or porridge, believing that they’re good for your health.

Wang Zhonghua and his colleagues dive for sea cucumbers in Dalian, Liaoning province. The seawater’s surface temperature is a chilly 2.5 degrees Celsius.

But harvesting sea cucumbers is a different story. Wang wears thick, cotton-padded layers beneath his wetsuit, but they make little difference against the frigid sea. Even when you clap your hands or hit yourself, he says, “you can’t feel any pain. That’s how cold it gets.”

When Wang started some 15 years ago, the sea cucumber aquaculture industry was still in its infancy. There was a lot of money to be made, and little awareness of the dangers involved, and so Wang and many others eagerly took the plunge.

After several years, however, Wang started to notice pain in his right leg and purple bruises whenever he’d come out of the water. He was diagnosed with osteonecrosis of the thighbone, a condition caused by a lack of blood flow. His doctor thinks it’s due to Wang repeatedly exposing his body to high water pressure, and suggested Wang change his line of work. He takes painkillers instead.

“No one who does this job knows how long they can keep on doing it.”

- Wang Zhonghua, diver

Nothing else pays as well, anyway. Last year, Wang rented a taxi and would work two jobs, collecting sea cucumbers in the morning and driving his taxi in the afternoon. But he says, “There’s not much money in cab driving — maybe 4,000 or 5,000 yuan a month if you work every day, and I have a wife and kid to look after.” Collecting sea cucumbers for a few months could earn him enough to pay for a whole year’s living expenses, so Wang shelved any plans of switching careers.

Sometimes, the islands’ divers die in underwater accidents. In April last year, one of Wang’s friends passed away. “No one knows what happened down there,” he says matter-of-factly, “and no one who does this job knows how long they can keep on doing it.”

Records of people eating sea cucumbers for medicinal purposes date back over 2,000 years to the Han Dynasty, with the animal being described in texts as beneficial to your organs. But sea cucumbers only became truly popular in recent decades as ordinary Chinese people had more and more money to spend.

Residents of the Changshan Islands say that, in the past, you didn’t need to go diving for sea cucumbers: You could pick them off the seashore. Few locals thought the odd-looking creatures were particularly valuable until the consumption boom in the 1980s, when they became both increasingly expensive and scarce.

A buoy field near Xiaochangshan Island off the coast of Dalian, Liaoning province.

When wild sea cucumbers became hard to find, fishers switched to aquaculture, buying young sea cucumbers from breeders and scattering them along the sea floor. After about three years, the animals — which hardly move during their lifetimes — are ready to be harvested.

The fishery Wang works for was formerly the Dalian state-owned fishery production brigade. Tang Shijing, the fishery’s former head, was one of the first to start cultivating sea cucumbers in Dalian. At the time, in the 1970s, few saw the economic sense of the trade. Public consumption of sea cucumbers was still low. “What’s more, at the at time, the oceans were teeming with fish — as if they’d never been exploited at all — so everyone wanted to go fishing,” Tang says.

Wang’s production brigade made its first forays into sea cucumber cultivation in the late 80s, constructing artificial reefs to create more suitable living environments. At the same time, people began turning the shallows into sea cucumber pools. The industry has grown to such an extent that every suitable stretch of coast in North China is now used for aquaculture, mostly to grow sea cucumbers.

Wang Zhonghua takes a break after diving for sea cucumbers near Dachangshan Island, Liaoning province.

This situation is cause for concern among ecologists. A report in 2012 by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) stated that coastline development had damaged over half of China’s coastal wetlands. These intertidal zones — which are submerged and exposed with the tide — are nutrient-rich areas that form stopover points for at least 33 “threatened” or “near threatened” waterbirds as they migrate between East Asia and Australia, the report says.

There are more than 1,200 known species of sea cucumber around the world. About 20 kinds are eaten in China, but the Japanese spiky sea cucumber is the most beloved, expensive, and widely cultivated.

Sea cucumbers, which feed on organic debris from the sludge of the ocean floor, are perhaps best-known outside of China for their peculiar defense strategy: When threatened, they expel some of their intestines in order to survive. They move slowly, covering only a few square meters of seabed during their entire lives, but their importance to the marine ecosystem shouldn’t be underestimated.

A worker shows off a fresh sea cucumber on Dachangshan Island, Liaoning province.

Dalian Ocean University lecturer Zhang Peng explains that sea cucumbers fill the same role as earthworms: They accelerate the decomposition of organic matter in the soil, and their own waste is food for microorganisms and other creatures that dwell on the seabed. In turn, they are food for marine animals above them in the food chain. However, most Chinese academic studies on sea cucumbers are focused on their breeding and nutritional value, with little attention paid to their survival in the wild.

China’s soaring consumption of sea cucumbers has contributed to a rise in their harvesting around the world. According to the “China Fishery Statistics Yearbook,” the country’s national output of cultivated sea cucumbers exceeded 200,000 tons in 2016. But that’s still not enough to satisfy demand, and so large amounts need to be imported.

From Ecuador to Indonesia, over 90 percent of the world’s tropical coastlines have joined the global trade in sea cucumbers. However, a 2011 study estimates that approximately 38 percent of the world’s sea cucumber fisheries are being overfished, and 20 percent are already depleted. Whenever one species of sea cucumber is overfished, fishers simply find another variety to take its place. After analyzing 377 sea cucumber species, the IUCN in 2013 listed seven species as being “endangered” and nine species as “vulnerable.”

A 2018 satellite map shows aquaculture ponds on the coast of Dalian, Liaoning province. From Google Earth

On the Chinese market, the phrase “caught in the wild” conjures up images of uncontaminated natural environments; however, even the sea cucumbers that have been artificially placed on the sea floor are labelled “wild.” Truly wild sea cucumbers are becoming increasingly rare.

“There are hardly any [wild] sea cucumbers left in the shallows; you can only find them if you go farther out,” says Wang.

SHANDONG, East China — Eighty-four-year-old retired fisher Li Shugan remembers clearly how the waters around Qingyutan Village were once teeming with Pacific herring. “You could throw an oar into the sea and it would stand upright,” he says. After a day at sea, the fishers’ baskets of herring would fill the beach. They would then slice open the fish’s bellies and remove the fish eggs — the meat generally being sold locally, with the eggs being exported to Japan and elsewhere.

But the fish is now so rare, few villagers younger than 30 have even seen a herring, says Li. The possible reasons for its disappearance are varied: overfishing, changing temperatures, and kelp — an edible seaweed that has taken over the local economy and coastal waters.

Qingyutan’s name is a reminder of the village’s fishing past — it means “qingyu beach,” after the Pacific herring’s Chinese nickname. Giant schools of this small fish are found all across the northern Pacific, from China to California. Decades ago, dense shoals of Pacific herring would migrate back to the waters around Qingyutan every March and April, allowing the fishers there to earn a good income.

Li remembers how he once pulled up a net with 35 tons of Pacific herring back in the 1970s. Since then, stocks of the fish have rapidly declined. “You can still see fishers catching a few now and then, but not very often,” says Li, who spent half his life chasing the Pacific herring.

Retired fisher Li Shugan sits at a mahjong table at his home in Rongcheng, Shandong province.

Pacific herring are sensitive to changes in the underwater ecology, and their numbers have risen and fallen throughout history in tandem with cooler or warmer weather. Average surface temperatures in March, when young herring hatch, have a distinct effect on population numbers, according to records of Pacific herring catches and sea temperatures over the past few decades, explains Li Yushang, a professor in the School of Humanities at Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

According to a longitudinal study conducted in a bay near Qingyutan, sea water temperatures rose on average 0.2 degrees Celsius per decade between 1980 and 2000. With global climate change accelerating, a continuing rise in sea temperatures might lead to Pacific herring spawning sites shrinking even further in the Yellow Sea.

Research by Li Yushang links the once-flourishing Pacific herring to the eruption of the Huaynaputina volcano in southern Peru more than 400 years ago. As one of the largest volcanic eruptions in recent history, it triggered a worldwide chain reaction that led to abnormal, years-long cooling in many countries, including China. The drop in ocean temperatures favored the Pacific herring, and population numbers in the waters near Qingyutan shot up.

Fishing boats come ashore in Rongcheng, Shandong province.

This also caused changes on land. Elderly fishers speak of how older generations said that inland residents of the Shandong peninsula were attracted by the bounty of the seas and gradually migrated to the coast. Historical studies have shown that the 17th century saw a surge in the formation of coastal villages.

Before the 1970s, the size of catches was limited, as fishers in Qingyutan still used traditional equipment. People would fish on the seafront using bamboo baskets, or they would throw handmade nets from their small boats. However, fishers soon started using bigger vessels with large, synthetic nets, allowing them to catch tremendous amounts of herring at once, especially during the periods when the fish laid their eggs.

China’s fishing industry was unregulated until 1987, when the government introduced a system of controls over the number and total power of fishing vessels, known as the “dual control” system. In 1995 it then also began to implement an off-season fishing ban in the Bohai, Yellow, and East China seas. Within these and other confines, ships are allowed to catch as much fish as they can.

Workers sun-dry kelp in Qingyutan Village, Shandong province.

But by then many fish stocks had already plummeted. Li Shugan, the retired fisherman, is able to reel off the names of numerous different fish that he used to catch — Pacific chub mackerel, Japanese seerfish, yellow croaker. Toward the latter stages of his career, in the 1980s, they were all in rapid decline.

Shandong University and other scientific institutions have conducted studies into the artificial breeding of Pacific herring. Wang Jun, a researcher at the Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute, remembers how one study was hampered because the fishers they commissioned to collect Pacific herring were only able to find 30 or so of the animals. After the year 2000, changes along the Yellow Sea coast were absolutely astonishing, he says. “Reclamation, aquaculture, and industrial sewage have destroyed many coastal wetlands, which are extremely important habitats for the fishing industry, and, if we don’t replenish [its species], cannot be naturally maintained.”

The Shandong coast used to be dotted with “seaweed houses” — brick-built homes with roofs covered in dried seaweed. These kept houses warm in the winter and cool in the summer, and lasted several years before needing to be replaced. Most of the seaweed used for these roofs was wild algae that naturally grew in shallow seawater. They provided the Pacific herring with a place to lay their eggs, but much of the shallows along the Shandong coast has now been taken over by artificially planted kelp.

At the beginning of the summer, rows of sampan boats bob up and down in the coastal waters off Qingyutan, as sailors drag huge amounts of kelp from the water and toss it aboard. In no time at all, the giant kelp leaves are piled higher than the people on the boat.

Rongcheng, the city that administers the tip of the Shandong peninsula where Qingyutan Village is located, is China’s largest kelp farming base, producing around half of the country’s annual yield. Kelp cultivation began in the 1950s, and, village elders say, had become the main industry by the 1980s. Rongcheng’s wealth of coastline means that the area has more than 1,300 square kilometers of coastal shallows suitable for kelp production.

Sixty-year-old fisher Zhang Huayue steers his boat out to sea in Rongcheng, Shandong province.

One of the fishers who took the lead when kelp production began was Zhang Huayue. “We used to spend the spring catching Pacific herring and would gather kelp in the summer,” he says. “Now it’s all kelp.” At the age of 60, he still rows his boat out to check how the kelp is growing every morning. He makes sure it receives the right amount of light, which is important for its growth; if it’s too strong, he’ll attach weights to the kelp so that it sinks down to darker waters.

In traditional fishing villages around the country, young people have moved out looking for better careers, leaving only the elderly and children behind. However, kelp requires large amounts of manpower to maintain and process, which has attracted many young people to Qingyutan in search of jobs. At dusk, as these workers bound out of the processing plants, Qingyutan brims with a vitality that few villages around China still possess.

Once the village became rich from cultivating kelp, it found that it had no more need for the seaweed. This impacted the fish — “Pacific herring lay their eggs near the seaweed and rocks. Now that the seaweed has gone, the Pacific herring can’t stay,” Li Shugan explains — and the architecture. After the turn of the millennium, large-scale remodeling led to neat rows of apartment buildings replacing the seaweed houses, until Qingyutan looked just like any new urban development in China. A handful of seaweed houses have been preserved, solely for the purpose of entertaining tourists.

A 2018 satellite map shows the rows of buoy fields used to plant kelp in Rongcheng, Shandong province. From Google Earth

The same tourists can ride fishing boats to scenic platforms out at sea to watch hundreds of people collecting kelp, and they can even give it a try themselves. The Pacific herring seems like something in the distant past. Only when the old fishers, now in their 70s and 80s, gather for a round of mahjong do tall tales of record catches resurface.

ZHEJIANG, East China — Before daybreak, fishing vessels return to the port of Shenjiamen on Zhoushan Island to deliver their catches to the largest fish market serving the East China Sea. As the ships dock one by one, workers drive over in their three-wheeled vehicles. Without saying as much as a word, they help the crew haul cases of fish ashore to be weighed. By sunrise, the city’s bustling morning markets open up, and the workers’ shifts come to an end.

Every year, when the fishing season nears its government-mandated summer hiatus, much of the catch is made up of small yellow croaker — migratory fish that visit these waters in late winter and spring to lay their eggs in the waters around the Zhoushan Archipelago.

Small yellow croaker have long been one of the most important fish to the Chinese maritime economy — and cuisine. On the Zhoushan islands, they’re eaten braised in soy sauce or simply steamed in clear soup. People used to dry them in the sun, too, but quit doing so when the price of fresh fish rose steeply, from 4 yuan per kilo a decade ago to 20 yuan now.

Fishing vessels dock at dawn to unload their catches at Shenjiamen’s market in Zhoushan, Zhejiang province.

The fishers of Shenjiamen say that the price increase is mostly due to falling fish stocks. Fisherman Wei Qiyong has just sold his final catch of the year. This season, he went out to sea nine times, earning a total of around 150,000 yuan — a good year. But, he says, this is entirely due to the soaring price of fish, as he actually caught fewer than in years past.

“Around 10 years ago, I’d go out and catch 10 or 15 tons, and now it’s more like 5 tons,” he explains. Much of this loss in volume is because the fish keep getting smaller. “It used to be that three small yellow croaker weighed half a kilogram; now, you need at least 10 fish for half a kilogram,” says Wei.

At the Shenjiamen market, most fish are tiny, with many of the small yellow croakers not even as long as the palm of your hand. The Zhejiang provincial government has set minimum sizes for fish that are allowed to be caught to avoid fish becoming food before they have had the chance to reproduce. For example, only small yellow croakers that weigh over 50 grams or are over 145 millimeters in length can be caught and sold. Many of those available at the market, however, barely seem to fulfill those requirements.

Workers unload small yellow croaker from a fishing boat in Zhoushan, Zhejiang province.

Since the mid-1990s, intensive fishing has exhausted China’s fisheries. At more than 1 million vessels at the end of 2016, the country has the largest fishing fleet in the world, accounting for one quarter of the global total. Approximately 260,000 of these are ocean-going vessels. The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs has estimated that a sustainable amount of fishing off China’s coasts is between 8 million and 10 million tons a year. However, the actual amount caught over the past two decades has greatly exceeded that figure, sometimes even reaching as high as 13 million tons.

According to the environmental group Greenpeace, about 4 million tons — or 30 percent — of the fish caught off of China’s coasts are young fish that haven’t yet reached maturity, a figure higher than Japan’s total annual catch.

Research has found that the small yellow croaker is reaching sexual maturity earlier and earlier in order to adapt to the intensive fishing. This is because fish that mature earlier have a better chance of reproducing before being caught, and so their genes have spread throughout the fish population.

Small yellow croakers brought back to Shenjiamen Port in Zhoushan, Zhejiang province.

In the 1950s, only 5 percent of the fish reached maturity around the age of 1. By the 1980s, this figure had reached 40 percent. Yan Liping, lead author at the East China Sea Fisheries Research Institute (ECSFRI), says that fish will change and evolve in order to adapt to their external environments, but this is not necessarily good news.

The acceleration in the speed at which small yellow croakers breed allows the fish to replenish the strength of the shoals, but this evolution toward earlier maturity has become less obvious since the 1990s, Yan’s research shows. This may mean that evolution has reached its limit in this case, and so if the intensity of the fishing continues to increase, it is highly likely that the fish will eventually become as rare as the large yellow croaker — a related species that has all but disappeared from Chinese seas.

In spring 1974, many state-owned fishing brigades along the coast carried out what was called a “major offensive” on the wintering grounds of the large yellow croaker, catching nearly 70 percent more than the previous year and leading to a sudden collapse in the population. Studies have found that even before the large yellow croaker’s stocks crashed, the fish had already begun showing signs of early-onset sexual maturity. But it couldn’t save the wild population. Now, most of the large yellow croaker being eaten in China come from aquaculture farms.

Dropping fish stocks has only increased competition among fishing boats in the East China Sea. In order to maintain a hold on good fishing grounds, Wei and several other captains from his village now join forces. Whenever one of the boats needs to return to port to unload its cargo, other boats remain in the area. “We have to stay, otherwise there’d be nowhere to cast our nets when we return,” he says.

People on the shore might think of the sea as practically boundless, but in the eyes of the fishers, it’s an extremely crowded place. Clashes between fishers are not uncommon, especially when they come from different villages. Wei recalls a time when his fishing net was deliberately cut. “There are too many boats, and before, boats only carried a few nets,” he says. “But now, one boat is capable of carrying several large nets.”

The occasional use of illegal fishing gear is an open secret. From the South China Sea to the East China Sea and the Bohai Sea, the fishers all say that, when they catch fewer fish, they can’t even cover the cost of their fuel, and so they’ll hang a smaller, finely meshed net inside their large fishing net to sweep up fish both large and small. Authorities rarely enforce rules that ban catching fish that are too small.

“The government’s policy is good, even though we don’t obey it ourselves. But there’s nothing else we can do,” Wei says with a sigh. Fishers all know that overfishing will inevitably lead to a collapse in fish stocks.

Wei Qiyong looks at his homestay in Liangshi Village, Zhoushan, Zhejiang province.

In order to protect offshore fisheries, the Chinese government introduced a seasonal ban on fishing in 1995. Fishing boats are prohibited from going out to sea for long periods during the summer breeding season, and every region has a quota for retiring and dismantling older fishing vessels to encourage fishers to take up other lines of work. In addition, the Ministry of Agriculture has announced a reduction in domestic marine fishing to less than 10 million tons by 2020 — roughly the same level as it was before 1995.

In Wei’s hometown of Liangshi Village, on Qushan Island, people are already looking for ways out of the fishing industry as the number of fish in the East China Sea dwindles. The village of more than 400 families used to have over 40 boats at its peak. Nowadays, however — as young people have gone to work in other cities, the elderly have retired, and fishers’ confidence in the industry has dropped — there are less than 15 vessels left.

The development of tourism has given Liangshi Village another opportunity. Chen Ridong, the village’s deputy Party secretary, opened the village’s first homestay in 2010. Over the subsequent two or three years, about 80 homestays of varying sizes have popped up in the village as Qushan Island, located two and a half hours away from downtown Shanghai, has become better known as a weekend getaway destination.

Liangshi Village is situated along a crescent-shaped sandy beach, behind which is a hill that offers picturesque views of the ocean below. The local fishers never thought of the place as anything special, but people from the city love the vistas. During last year’s National Day holiday, when nearly everyone in China has a one-week vacation, there wasn’t enough accommodation to house all the visitors.

“The government’s policy is good, even though we don’t obey it ourselves.”

- Wei Qiyong, fisher

Wei and his wife also saw their opportunity, and opened their homestay last year. But, like fishing, their new business is dependent on the weather. The summer months, which line up neatly with the fishing hiatus, are busy. But the cold winters attract few tourists, and so fishing is still more lucrative than the homestay business.

While repairing his fishing boat, Wei ponders how the number of fish will surely decrease in the future and how he might have to “go ashore” sooner than he planned. However, people like him, who became fishers straight after middle school, have few other skills. “If we returned to shore, what would we do? Wei says. “There’s nothing we can do.”

FUJIAN, East China — At 4:30 a.m., dozens of motorbike headlights illuminate the dock in Oucuo Village, located opposite the harbor from Xiamen, the region’s largest city. Several dozen fishers — decked out in waterproof overalls and equipped with hoe-like fishing tools, bamboo baskets, and buckets — arrive, jump aboard their boats, and set off to catch lancelets.

Most of China’s fishing fleet has been upgraded with advanced equipment and larger nets. But fishing for lancelets is different, explains fisher Wang Zhiping, who says the equipment they use was handed down by their fathers and grandfathers.

Fully grown, lancelets are the size of toothpicks — so small that you can hardly feel the weight of one in your hand. They are now a rare and valuable delicacy in Xiamen. However, before the 1980s and particularly before the 1950s, this unassuming creature could be found on many Xiamen dining tables, where it was used to freshen the palate alongside soup and noodles. At that time, Xiamen was the world’s biggest lancelet-producing locale, with an annual catch of more than 280 tons at its peak.

Nowadays, only the old fishers in Oucuo will go out of their ways to catch lancelets. Over half an hour by boat east from the coast is a curved sandbar where lancelets can be found. After dropping anchor, Wang enters the water, putting his basket and bucket on a bamboo raft which he ties to his waist. Today is “neap tide,” one of the 10 or so days of the month when the water is low enough — it reaches only to the fishers’ thighs — to make collecting lancelets possible. Wang swings the hoe toward the seabed, lifting up the sand and tossing it into his basket. After doing this several times, he filters the sand out, and what’s left are the small, wriggly lancelets. Scattered across the sandbar, his fellow fishers repeat the same motions.

Fisher Wang Zhiping has to work harder than ever to scout out lancelets, since their habitat has been steadily shrinking since 1950.

At around 9 a.m. the tide rises, and everyone heads back home. Wang’s catch fills a third of a bottle, roughly between 50 to 100 grams, he reckons. Back when he started fishing for lancelets with his father in the 1980s, they could get 250 grams a day. His grandfather, many years before, could collect 4 kilograms in a single day.

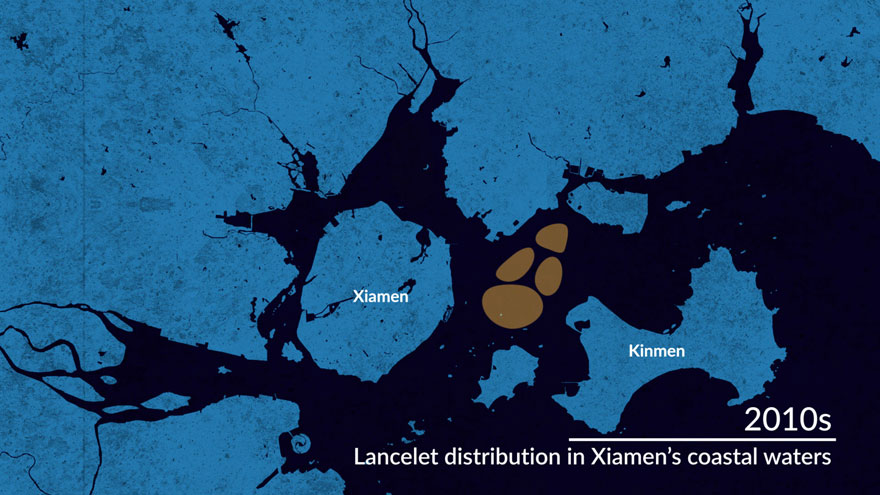

Multiple studies show that the Xiamen lancelet fishing grounds declined due to the construction of a high seawall in 1955 and the land reclamations that followed. The seawall linked Xiamen, which is built largely on an island just off the Fujian coast, to the mainland. The wall’s eastern part cut right through the once-famed Liuwudian lancelet fishing grounds. Only a narrow channel was left open.

Within a few years, people realized the seawall blocked the tide, reducing the sea’s ability to refresh itself. Nevertheless, it wouldn’t be until 2010 for the dam to be turned into a series of bridges in an effort to improve water quality. But this came too late for the tiny lancelet. Yearly catches had dropped from over 54 tons in 1957 to just several tons in 2010, and have not recovered since.

Wang Zhiping hunts for lancelets in Oucuo Village in Xiamen, Fujian province.

For biologists, lancelets have more value than just as food. They discovered that this species has existed in the oceans for over 500 million years, making lancelets true living fossils. They represent an important link in biological evolution — the transition from invertebrates to vertebrates.

Despite appearances, lancelets are not, in fact, fish. They have a notochord running the length of their bodies — a cartilaginous rod that is the predecessor to the spine in vertebrates; through it runs a nerve tube, which is the animal’s nervous system. They also do not have an obvious head, only a simple brain-like swelling at the front of the nerve tube. Biological studies suggest that it is from this kind of rudimentary form that life evolved into more advanced, diverse vertebrates — including humans — who evolved skeletons as well as more complex nervous systems.

Lancelets are studied at the Ocean and Fishery Research Institute of Xiamen, Fujian province.

This special status makes the lancelet a hot topic for research. At Xiamen University’s Xiang’an campus near Liuwudian, Professor Wang Yiquan, of the School of Life Sciences, has built a special laboratory for the study of lancelets. He explains that scientists believe vertebrates appeared roughly 400 million years ago, but exactly when and how they evolved from invertebrates remains a mystery.

Wang Yiquan’s lab is conducting experiments on lancelets, either removing or implanting genes to see how they develop in an attempt to discover more about the unsolved mysteries of how species evolve. A recent study used lancelets to find out which genes are responsible for the differences in development between an animal’s left and right sides.

Over the past few decades, many scientific institutions have attempted to breed lancelets in the laboratory, and have mostly failed. But chief engineer at the Ocean and Fishery Research Institute of Xiamen (OFRI), Zhou Renjie, hopes that his laboratory can help return lancelets to Xiamen’s waters using large-scale breeding methods.

Lancelets generally half-bury themselves in the sand, eat small algae which they filter from the water, and lay their eggs at the beginning of every summer. After hatching, the young lancelets spend about a month floating around, after which they need to find a suitable patch of sand where they can change into bottom dwellers. During this process, the mortality rate of young lancelets is extremely high.

A man strolls along the beach of Gulangyu Island in Xiamen, Fujian province.

Zhou originally wasn’t hopeful, seeing the lack of prior success, but his setup of large metal cauldrons of sand, seawater, and seaweed proved fertile ground for lancelets. The first year the OFRI officially launched large-scale tests, they produced over 200,000 young lancelets come summertime. By the end of the year, they were released into a protected area for lancelets.

The program has continued, releasing millions of animals every year. However, according to a publication affiliated to the Xiamen Oceans and Fisheries Bureau, the number of lancelets has only begun to increase again during the past few years after declining for most of the decade. In 2010, there were approximately 112 lancelets per square meter observed in the main protected area, but by 2017, this number had dropped to just 45 per square meter.

“The lancelets and the people live too close together.”

- Zhou Renjie, researcher

Zhou explains that lancelets are an indicator species for the ocean, since they have relatively strict requirements for their living environments, favoring shallows with clean, loose sand. However nowadays, these exact same places are also hot spots for urban expansion and development. Not far from Liuwudian, dredging boats operate off the coast, extracting sand for use in the ongoing buildup of Xiamen and other cities. For the lancelets, such activities are a disaster. The protected area is badly enforced, and the seaflats are frequently disturbed by tourists on jetskis, and even fishers.

In Zhou’s opinion, artificial breeding and areas completely free from human disturbance are key for the lancelet’s survival in the wild. However, in today’s highly urbanized Xiamen, finding such places are extremely difficult. “What can you say?” Zhou says. “The lancelets and the people live too close together.”

HAINAN, South China — In 2009, Zhuo Qihui, then a student in Beijing in his early twenties, saw a piece of news saying Hainan’s mud crabs were on the verge of disappearing. Having grown up in a fishing village on Hainan, Zhuo used to be able to simply put his hand into the sea and pluck them out. So, how could there not be any left?

Together with four childhood friends who were also living in Beijing, Zhuo went back to Hainan during a holiday to see for himself. What they found was pollution along the coastline from aquaculture pools that are used for the intensive breeding of crab, shrimp, and other seafood. The students spoke to breeders and tried to persuade them to change their methods, but were simply told they “didn’t understand how things worked.”

The experience inspired them to try and develop a sustainable way to breed mud crabs, which are locally known as Hele Crabs. In 2011, they set up the Hainan Wanning Hele Crabs Conservation Center, hoping to promote ecological breeding across the whole region, halt pollution, and rebuild an ecological coast.

CEO Zhuo Qihui examines a mud crab at the Hainan Wanning Hele Crabs Conservation Center in Hainan province.

Mud crabs are found in their largest numbers off of Hainan’s southeast coast. They are loved for their creamy and sweet crab roe, and are considered one of the island’s four most famous dishes.

In the eyes of ecological researchers, mud crabs aren’t just a delicacy, but an indicator species for mangrove forests — unique ecosystems that consist of trees that grow in coastal waters across the tropics and subtropics. Wu Bin, a researcher at the Guangxi Mangrove Research Center, explains that a healthy population of mud crabs means a healthy mangrove, too: “Mud crabs are apex predators, like tigers in the forest.”

Mangroves provide shelter for marine organisms, and protect the coastline and coastal regions from the effects of climate change and extreme weather. However, few people in China recognize their importance. The country’s first mangrove reserve was established in northeast Hainan in 1980. But this did not prevent more mangroves from disappearing in the ensuing boom of pond aquaculture and land reclamation.

Nowadays, half of the world’s aquatic food is cultivated, and China contributes over 60 percent of that number: With production exceeding 5 million tons in 2016, the country is the largest supplier of aquaculture seafood in the world. The Chinese government has supported development of coastal aquaculture for several decades and has made the building of super-sized sea pastures an important development strategy. But this has come at the expense of coastline ecosystems. The 2016 National Wetland Conservation 13th Five-Year Action Plan revealed that mangrove coverage had been reduced by over 73 percent since the founding of the PRC in 1949.

A view of Gangbei Port in Hainan province.

Xiaohai, near Hainan’s Wanning City, is one of China’s largest lagoons, at close to 50 square kilometers. The body of brackish water is embedded in the center of the island’s east coastline and connects to the sea through a long, narrow, and winding waterway. Xiaohai used to be surrounded by lush mangroves, but these have since been developed into docks, villages, and fish ponds.

In recent decades, as fishers all along China’s coastline faced dwindling catches, many were left with no choice but to find other work. The 1980s and ’90s saw a boom in the development of mudflats, which are made of soft terrain and are cheap to redevelop. Many retired fishers — as well as other people who smelled a business opportunity — turned the coast into a series of ponds. Xiaohai, a natural salt-water reservoir, was prime aquaculture real estate.

The Wanning government diverted the Taiyang River — which flows into Xiaohai and provides it with fresh water — toward the sea in the early 1970s as a way to control flooding. However, people soon realized the nearsightedness of the project. Xiaohai’s water quality dropped. Then, as intensive aquaculture expanded on its shoreline, the ecology of the lagoon became further unbalanced.

Yandun Village, to the north of Xiaohai, has undergone dramatic changes because of aquaculture. Breeder Ye Caijun explains that locals were never good at fishing, and were “so poor that women didn’t want to marry into the village.” Now, to the envy of neighboring villages, everyone in Yandun is a big-time breeder.

The Ye family’s pools are teeming with hundreds of thousands of young shrimp. They are connected to Xiaohai via simple water pumps and ditches which refresh the water every week. When the water flows out, it’s heavily polluted with feces, dead animals, and medicine. Because there are so many animals in such a small area, aerators need to work nonstop to prevent the fish and shrimp from suffocating.

Zhuo Qihui checks on the mangrove saplings he planted a year ago in the crab breeding farm in Wanning, Hainan province.

In Xiaohai, Zhuo, the former Beijing student, frequently sees breeders indiscriminately throwing medicine into their ponds. If veterinary drugs don’t work, then they’ll use antibiotics made for human consumption, infuriating Zhuo. One time, when talking to a breeder, he jumped up and asked, “Do you dare eat what you’re growing?”

Breeders are both the culprits and victims of pollution, which has made aquaculture a risky business. Ye explains that, decades ago, when the water quality wasn’t too bad, the shrimp grew well. But now, due to pollution or sudden outbreaks of disease, sometimes over a hundred thousand animals die all at once.

Han Han — founder of the private think tank China Blue, which focuses on promoting the development of a sustainable fishing industry in China — says that environmental pollution and food safety are intractably linked. “When breeders can’t maintain sustainable production and operations using normal methods and so resort to sacrificing the environment for profit,” Han says, “the food safety problem appears on the consumer’s end.”

“When breeders […] resort to sacrificing the environment for profit, the food safety problem appears on the consumer’s end.”

- Han Han, think tank founder

But consumers haven’t caught on to how dirty the nation’s aquaculture ponds are, and the price of seafood remains high. “As long as you can breed them, you never have to worry about selling them,” Ye says.

At Zhuo’s crab conservation center, the mud crab pools are also separated from Xiaohai by just a single dam, but the water passes through three purification pools with different kinds of algae. This cleans the water of its unnatural abundance of nutrients. To ensure that every crab has a reasonable amount of living space, Zhuo and his business partners have greatly reduced the breeding density and thus the waste.

Mangrove trees line the pools, which the crabs share with different kinds of fish. This creates miniature ecosystems that are ideal for the mud crabs, which can also purify the water on their own. The center produces very little waste.

A 2018 satellite map shows fishponds along the shore in Wanning, Hainan province. From Google Earth

But Zhuo’s biggest goal is restoring the mangroves along Xiaohai, starting from the edges of the center’s crab ponds. China has started to promote wetland restoration projects in areas where mangroves have already been destroyed. The National Wetland Conservation 13th Five-Year Action Plan aims to restore the mangrove forests to their former levels, at the founding of the PRC, by 2020. However, Wu Bin of the Guangxi Mangrove Research Center is skeptical, pointing out that most of the land suitable for mangroves has become aquaculture ponds in the past few decades.

On the edge of Zhuo’s farm, a few small mangrove trees sway in the wind. “There were some bigger mangrove trees there, but they were pulled out,” he says, pointing to a stretch of naked shoreline. Due to China’s system of rural land ownership, many of Zhuo’s ponds are rented from different households. As soon as the lease of some ponds expired, the farmers uprooted the mangrove, Zhuo says. “They felt the trees were in their way.”

WORDS Shi Yi PHOTOS & VIDEOS Wu Huiyuan, Xie Kuangshi TRANSLATORS David Ball, Yang Ziyu STORY EDITOR Kevin Schoenmakers COPY EDITOR Hannah Lund

PRODUCT MANAGER Lü Yan PHOTO EDITORS Ding Yining, Jiang Jin VIDEO EDITORS Chen Xi, Han Xinyu DATA EDITOR Zou Manyun POST-PRODUCTION Zhang Zehong, Jiang Yong

ART Huang Wei, Long Hui, Zhang Yue, Wang Yasai WEB Lin Tao DESIGN Fu Xiaofan QUALITY CONTROL Wu Yingyan, Chen Ronghui