Shocking allegations tore apart a northern village. Ten years on, the nation still wonders what really happened with Tang Lanlan.

July 27, 2018

WORDS Fan Liya VISUALS Tang Xiaolan

I. Mass Arrest

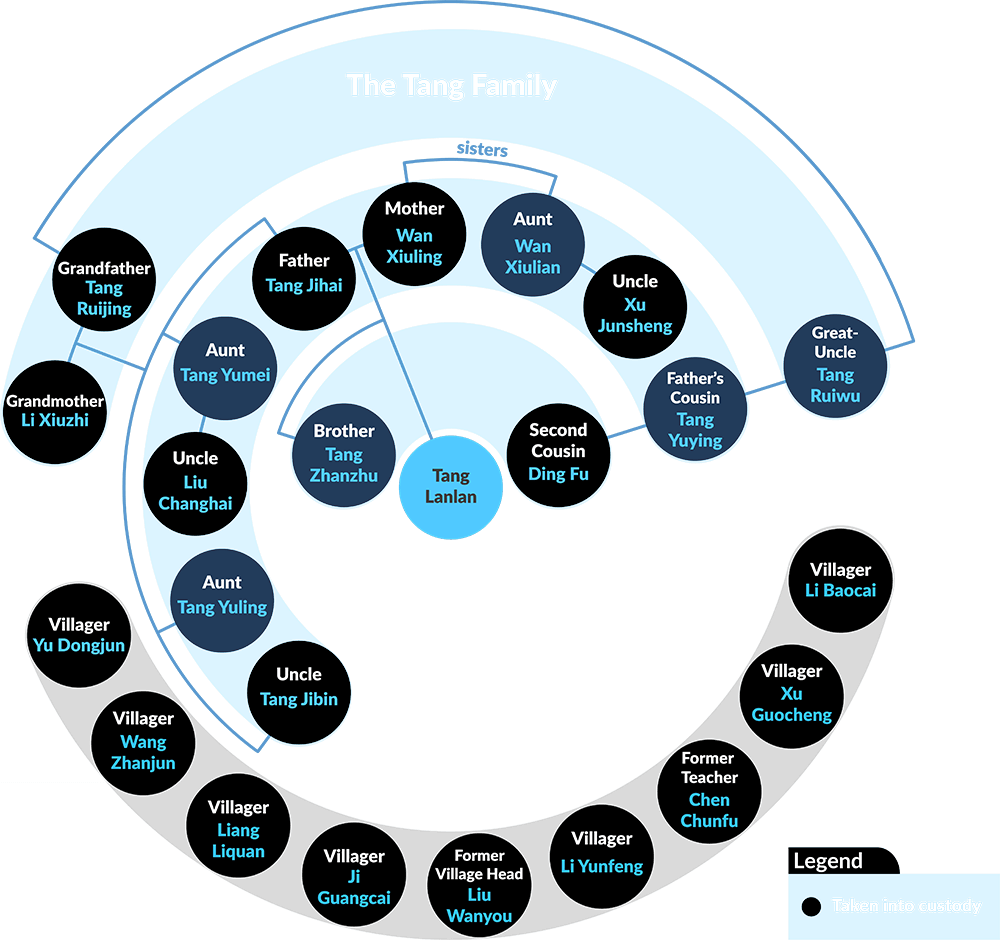

In late October 2008, the village’s slow-paced farming life was jolted by the arrival of out-of-town police. In swift succession, they took 17 people into custody, including the girl’s parents and many of her relatives and neighbors. At the time, villagers tell Sixth Tone during recent interviews, nobody had any idea what was going on — and they still don’t fully understand.

Some of the villagers connected to the case. Almost every family in Donglongshan is related to the victim or one of those accused.

Some of the villagers connected to the case. Almost every family in Donglongshan is related to the victim or one of those accused.

Tang Yumei, the girl’s aunt, was tucking her 10-month-old son in for a midday nap when police appeared at her home to apprehend her husband. She remembers her confusion: “I thought he might have violated some kind of land regulation when he grazed cows in the mountains,” she says.

Tang didn’t know then that police had already taken away several of her family members, including the girl’s parents, and would soon return for the girl’s grandfather and three more men. By evening, the only male members of the family who had not been apprehended were Tang’s son and a 5-year-old nephew.

When 50-year-old migrant worker Lu Zhandong returned home days after the mass arrest, he discovered the whole village in a panic. “Young men in the village were so frightened, thinking any one of them could be next,” says Lu.

Earlier in the month, police had received a letter from a 14-year-old girl who is now known by the alias “Tang Lanlan.” She wrote that her father and other male villagers had repeatedly raped and gang-raped her over a period of seven years. Her mother and grandmother had not only turned a blind eye — they had profited, charging male villagers 50 yuan ($8) to have sex with her.

“My father said that to continue my studies, I had to submit to them,” Tang Lanlan wrote. “Whenever I disobeyed even a little, they would beat me.” She listed 10 male villagers — including her grandfather, uncle, and primary school teacher — as her abusers.

II. The Village

Like many of the settlements scattered across the Northeast China Plain, Donglongshan was built from scratch by migrants.

Tang Lanlan’s grandfather, Tang Ruijing, was among the pioneers who cleared the wilderness and built the first houses. In 1959, when he was just 12 years old, Tang Ruijing and his family fled famine in their native Shandong province, in eastern China, and joined a wave of migration to the northeast, over a thousand kilometers away. There, large patches of sparsely populated forest were waiting to be turned into arable land.

The Tang family, like most other families in the village, first settled down near Wudalianchi, the area’s biggest city. In the 1970s, an outbreak of disease spread through contaminated water sent the family packing again, and they moved to what is now Donglongshan, less than 100 kilometers from the Russian border.

Snow still blankets Donglongshan in late February.

“The place was filled with woods and grasses,” recalls 79-year-old Liu Cun, whose family is from near Beijing. It took four months for people to fell the trees and move in. The first year’s harvest was poor, he remembers, and many people got sick from eating the low-quality wheat.

“Back then, we had a hard life and had to work from dawn till dusk,” Liu says. “Later, when we had more land, life became better. We moved into brick houses and had running water.” Even today, some families live in homes made of wood and sheet metal, and use water pumped directly from the ground.

The acres of wheat and soybeans remain the major source of income in the village; many younger residents move away to find more secure employment in towns and cities. The exodus has left the population virtually unchanged from decades ago.

III. The Tang Family

Tang Lanlan’s mother, Wan Xiuling, was just 19 years old when she got married in 1992. The young couple, who had met through a matchmaker, lived with the extended Tang clan and helped with the farmwork.

Tang Lanlan was born in the fall of 1994 — the first grandchild in the family. “Because the rest of us weren’t married then, we treasured and pampered her,” her aunt Tang Yumei says. She remembers buying the girl new clothes for Chinese New Year.

In Tang Yumei’s eyes, the girl grew up in a happy and harmonious family. But in 2001, following a farming dispute, her parents unexpectedly divorced, citing “incompatible personalities.” Wan left for state-owned Erlongshan Farm more than two hours away by car, where her own parents lived. Several months later, she came back to collect Tang Lanlan, who started kindergarten at Erlongshan in September that year.

People share their impressions of Tang Lanlan.

After a brief separation, Wan returned to Donglongshan in November that year. She and Tang Lanlan’s father remarried and had a son two years later. Meanwhile, Tang Lanlan continued her education at Erlongshan, staying with her grandparents.

Now and then, Tang Lanlan would visit her mother’s younger sister, Wan Xiulian, who also lived at Erlongshan Farm. Wan Xiulian says that because she is infertile, she and her husband, Xu Junsheng, doted on their niece, whom she remembers as “thoughtful and well-behaved.” She was shocked when Tang Lanlan accused Xu of raping her in the cowshed when she was in first grade, and again in their home. The couple divorced in 2017, under pressure from Xu’s relatives who blame Wan Xiulian for his imprisonment.

IV. Moving to Town

Tang Lanlan transferred schools four times during her primary school years. During second grade, she moved back to her parents’ home in Donglongshan. But the village school — like many rural schools in China — closed due to diminishing student numbers around 2004, so children from Donglongshan had to study in nearby towns and cities.

In September 2007, then-13-year-old Tang Lanlan moved to Long Town for sixth grade. Because the school was more than 80 kilometers away from Donglongshan, she boarded with a host family and returned home only for holidays — when, according to her letter, the abuse continued.

Though larger and more modern than Donglongshan Village, Long Town has only one major road, lined with stores selling chemical fertilizers and agricultural equipment. Close by sit the single-story house of the host family where Tang Lanlan and other students lived, and the primary school they attended.

Wan Xiuling and her husband seldom visited their daughter. Busy with farming, Wan Xiuling would drop by only when she went to Long Town to buy fertilizer during the sowing season in May. They paid the host family a monthly accommodation fee of 300 yuan.

Wan Xiuling remembers the first time she met the host mother, Li Zhongyun. “She seemed friendly and told me not to worry about my child staying with them,” says Wan Xiuling.

The deserted site of the primary school Tang Lanlan once attended in Long Town.

There were fewer than 10 students living with the host family then, according to 24-year-old Cai Qichao, another boarder from Donglongshan Village who stayed with the family for over two years beginning in 2006. During their free time after school, the students would either wander around the neighborhood or hang out at an internet café.

Tang Lanlan grew close to her host parents. Several months after she moved in, she started calling Li and her husband, Wang Fengchao, her godparents. Nearly every month, Tang Lanlan would go with them to a Buddhist temple in another town. “Every day, the family would light incense in prayer,” Cai says. “She was the only one of us who joined the worship.”

V. The Confrontation

The summer before Tang Lanlan was due to start middle school, she didn’t return home for the school holidays. She told her mother she was busy with English classes. Her mother did not accompany her to register at Long Town Middle School in September 2008 either, because she was busy with the wheat harvest.

Long Town Middle School is about 20-minute walk from where Tang Lanlan boarded with a host family.

Shocking news arrived on Oct. 1. While Wan Xiuling and her husband were out in the fields harvesting soybeans, Tang Lanlan called and said that she was pregnant. The father, she said, was her own dad, Tang Jihai. Wan Xiuling remembers her husband saying, “What bullshit!” when he overheard the conversation. Both assumed that their daughter had gotten involved with a boy at school.

Worried, Wan Xiuling traveled to Long Town two days later, accompanied by her husband’s cousin. “She asked me to go with her to bring back her child, who was pregnant,” recalls 65-year-old Tang Yuying. No one else in the family knew of the pregnancy.

Tang Lanlan was sitting on her bed when Wan Xiuling and Tang Yuying arrived at the host family’s house. She started crying when her mother tried to take her away. “I told her if she had been bad at school, she should quit studying and come home with me,” Wan Xiuling says. “She promised to be good.” Wan Xiuling herself had left school after the second grade.

Decorations cover the gate of the host family’s house at Chinese New Year.

When Tang Lanlan resisted, her mother slapped her. Li, the host mother, then took Wan Xiuling aside and told her that Tang Lanlan had gotten an abortion in March.

Wan Xiuling says that when she gave up and started to leave, Tang Lanlan said to her, “Mom, I’m going to put all of you in prison.” According to court records, Tang Lanlan wrote her letter to police that same day, Oct. 3.

VI. Investigation

A few weeks later, at the Wudalianchi police station, Wan Xiuling was at a loss when asked to confess. “I said nobody in my family ever got up to any trouble,” she says. “We’re honest folk; all we do is farm.” After waiting for hours in the interrogation room, Wan Xiuling was told that both her husband and others arrested had admitted to raping Tang Lanlan, and that she was accused of forcing her daughter into prostitution. When she denied the accusation, she claims a policeman slapped her and kicked her to the ground.

After midnight, a police officer handed her a piece of paper, telling her that they would release her if she signed it. Wan Xiuling, who says she can barely read, believed him. But as soon as she signed it, she was told that it was an admission of guilt. “I was so shocked that I slumped to the ground,” she says.

When Liu Wanyou, then the village head of Donglongshan, was told by police that Tang Lanlan had accused him of rape, he thought the Tang family must have framed him because of a legal dispute over a piece of woodland. But when he heard that the girl’s own parents and relatives had also been arrested, he was baffled.

Wang Xiuling and Yu Dongjun talk about their experiences in detention.

Liu Wanyou, now 48, remembers Tang Lanlan as a polite child who always said hello, but adds that they had few interactions. “I’m still in the dark about why this little girl would put her parents and all these people in prison,” he says.

The former village head says police beat him during his interrogation. Though the incident took place a decade ago, he says he remembers it like it was yesterday: “They lifted up my shirt, took off my leather belt, soaked it in water, and lashed my back with it.” He says they also slapped him and put a plastic bag over his head.

Tang Lanlan’s grandfather, Tang Ruijing, died on Dec. 13, 2008, after a month in custody. According to his daughter Tang Yumei, he had a bout of tuberculosis shortly before he was detained, but the police refused the family’s requests to send him medication.

VII. Sentences and Appeals

During their first trial at the Heihe Intermediate People’s Court in 2010, the suspects denied the accusations and said they had been forced to confess during their interrogations. But based on their confessions and testimonies from Tang Lanlan, the police, and other witnesses, the court ruled that there had been eight instances of rape between 2000 — a year earlier than Tang Lanlan had claimed in her letter — and 2008. Medical examinations determined that Tang Lanlan had experienced repeated sexual intercourse.

The girl’s mother, Wan Xiuling, was sentenced to 10 years in prison; her uncle Liu Changhai was sentenced to 15 years. Tang Lanlan’s father, Tang Jihai, received a life sentence. All the convicts appealed, but the high court of Heilongjiang province upheld the original verdict in 2012 — though some later had their sentences reduced for good behavior.

Where Are They Now?

Final adjudication in 2012:

Status:

*the crime was abolished in 2015

With her husband, brother, and father among those accused, Tang Yumei has never given up her efforts to clear her relatives’ names.

“If [Tang Lanlan] really suffered, it would be shameful for me to say these people are innocent,” Tang Yumei says. “I’d have to be sick to appeal for them if they raped the child. I am not insane.”

For years, further attempts to appeal were rejected, with the courts responding that the case had been closed with sufficient evidence after a fair two-year investigation.

Then, in early 2018, came a breakthrough.

VIII. Spotlight

In January this year, Chinese media brought the 10-year-old case to public attention after interviewing some of the released convicts. Investigative reporting raised questions and pointed out flaws in the legal procedures.

According to court records of the trial in 2010, Tong Bin, the cellmate of one of the convicts, Ji Guangcai, testified that Ji told him he had raped Tang Lanlan three times. But in an interview with The Beijing News in February 2018, Tong said he had never testified for anyone. He denied even knowing Ji.

Wang Danyang, the defense lawyer for Wan Xiuling at the 2010 trial, told Sixth Tone’s sister publication, The Paper, that key evidence supporting the defendants had been ruled inadmissible. One example was the recording of a phone call in which Tang Lanlan told a distant relative, Cai Xiangling, that she would accuse him of rape unless he paid her hush money.

“I feel angry every time I think of the call,” says 49-year-old Cai Xiangling, who refused to pay up. “Why would I hurt her? She’s the same age as my own child. I am not that kind of person.” The call came several days after the mass arrest, while Cai Xiangling and his wife were at the grocery store. Another villager recorded the conversation, but though they reported it to the police, Cai Xiangling says the police never contacted them about it, and the girl never followed through on her threat.

Cai Xiangling, a distant relative of Tang Lanlan, claims she threatened to accuse him of rape.

Media coverage of the case shocked readers. The story sparked widespread debate on the ethics of journalism, the protection of child rape victims, and the legal process. While at first, many slammed journalists for violating Tang Lanlan’s privacy and for seemingly siding with the accused, public opinion later shifted to questioning whether the case was a miscarriage of justice.

Legal experts argued for a review of the case. “The emergence of new evidence has shaken the credibility of the facts confirmed at the trial,” wrote Cheng Lei, an associate professor at Renmin University of China’s law school, in a commentary for news outlet Caixin. In his opinion, dubious legal procedures surrounding the case have damaged the credibility of the justice system at a time when the public demand for truth has never been stronger.

China has overturned numerous wrongful convictions as part of the government’s recent focus on judicial reform and the “rule of law.” More than 6,700 cases had their sentences changed following retrials in the last five years. Yet the conviction rate of Chinese courts remains high: More than 99.9 percent of criminal suspects are found guilty.

Copies of Tang Lanlan’s accusation letter, sent Oct. 3, 2008.

At the same time, child sexual abuse is underreported in China as elsewhere, and few reported cases result in criminal prosecutions even today, when public awareness and professional expertise are much greater than 10 years ago. Though experts stress that minors can give reliable testimony if questioned appropriately, police often dismiss allegations that rely on a single victim’s account.

In 2013, the Supreme People’s Court issued a judicial explanation on handling such cases after an enormous public outcry that year over the rape of six primary school girls by a principal and a government official in China’s southern Hainan province. Yet according to Zheng Ziyin, deputy director of the Guangdong Lawyers Association specialist committee on child law, prosecutors still complain of “unprofessional” police investigations.

Child sex abuse should be treated differently from other crimes, Zheng says, as sexual assault of minors typically takes place in secret, victims often cannot express themselves clearly, and evidence is easily lost. With regard to the Tang Lanlan investigation, he says the case cannot be judged solely on the testimony of the released convicts, but he hopes that a judicial review will help push for more thorough, specialized investigations of child rape allegations and “reveal the facts to the public.”

Tang Lanlan’s grandmother, Li Xiuzhi, is now 73 and barely recalls her arrest 10 years ago.

The grandmother’s statue of Guanyin, the goddess of mercy in Chinese Buddhism, with offerings of fruit.

After widespread national coverage of the Tang Lanlan case, the political and legal affairs commission of Wudalianchi’s municipal Party committee accused Wan Xiuling and others released from prison of seeking media attention to pressure local authorities. Some news stories on the case were suppressed.

In late February, Heilongjiang’s high court accepted the appeal of four convicts — including Tang Lanlan’s father, Tang Jihai.

Tang Jihai’s attorney, Deng Xueping — who has worked on several high-profile cases including the suspicious death of Lei Yang in police custody in 2016 — released a statement in March. “Based on the [investigative] work we have done, we think the case involves seriously unjust, false, and erroneous charges that are based on forced confessions and depart from common sense,” Deng wrote.

In late May, Deng released another statement saying that the high court had spoken with Tang Lanlan as part of its review.

But after a five-month investigation, the court announced on July 27 that it would not retry the case. The 2012 verdict was upheld, the court said, because the facts were clear and the evidence sufficient. “There is nothing improper about the original judgment, which determined the convictions and the sentences for the appellants according to the law,” it said.

Tang Jibin, Tang Lanlan’s uncle, says that they plan on taking the case to the Supreme People’s Court. “We suffered such an injustice, and must keep appealing,” he tells Sixth Tone, following the decision not to hold a retrial.

IX. Release

In Donglongshan Village, few believe that things happened the way the court says.

When former village head Liu Wanyou was released from prison, many locals came to greet him, which he sees as an affirmation of his innocence. “The villagers invited me for meals and dropped by for chats,” he says. “If I had committed the crime, nobody would come over or invite me for meals.”

Tang Yumei now lives with her two children and the parents of her imprisoned husband, Liu Changhai. Her daughter is in college, and her son — a baby when his father was taken away — will soon graduate from primary school. Left to take care of both the young and the old alone, she says she feels worn out but will not stop fighting until justice is served.

Tang Yumei poses for a photo at her home in Donglongshan.

A discarded red lantern sits in the snow after Chinese New Year in Donglongshan.

“If there really were someone like that in our midst, if anyone had really done such things to this child, it’s impossible that I would never have noticed anything in all these years,” she maintains.

No one in the village has seen Tang Lanlan in recent years. The last time Tang Yumei saw her was at a store in Long Town in 2014, but the girl said she didn’t recognize her.

Sixth Tone visited Tang Lanlan’s host family in Long Town in late February. The father, Wang Fengchao, refused to let the reporters in. He said that Tang Lanlan had left the household after graduating from middle school. His wife, who he had at first claimed wasn’t home, then emerged and asked the reporters to leave or she would call the police.

Yu Dongjun, who was released in 2013, poses for a photo at his home in Donglongshan.

The setting sun almost seems to kiss the snow in Donglongshan Village.

Although Wang Fengchao said that he hadn’t seen Tang Lanlan again since she left around 2011, a neighbor told Sixth Tone that he saw her visiting the family in 2016, when the host parents’ daughter got married. The neighbor declined to give his name, citing privacy concerns.

Tang Lanlan’s mother, Wan Xiuling, was released in June 2017 and now works at a supermarket in Dalian, a city on China’s northeastern coast about a thousand kilometers from home. She says all she wants is to prove the innocence of those accused. She also hopes to see her daughter, now 23, again.

“I’ve never changed our cellphone number, in case she calls us someday,” Wan Xiuling says.

X. Ruins

At the edge of Donglongshan lives Tang Jikui, 71, who used to teach at the village primary school. He is a distant relative of Tang Lanlan, knew her grandfather well, and thought her father and uncle were “good boys.” But he nevertheless sees the case with a coolness only a northeasterner could muster. “The police, courts, prosecutors — if the verdict is incorrect, none of them should get away with it,” he says. “If the rapes actually happened, then the family members are beasts.”

As dusk falls, houses in the village light up one by one, and wisps of smoke rise from their kitchens. Across from Tang Jikui’s house stands the mud cottage where Tang Lanlan, her parents, and her little brother once lived. Since the arrests, it has been abandoned. Walls have collapsed, and the house’s wood-and-brick frame leans heavily to one side. Weeds grow waist-high in the snow-covered yard.