HEILONGJIANG, Northeast China — Wu Fengqin’s husband groans as she shows his hands to the camera. Li Chen’s stubby, weathered fingers seem to resist being unfolded, almost as if they’d been fused together.

These aren’t the hands of the man she married 48 years ago, Wu explains. Instead, they’re the product of a chance encounter with Japan’s toxic colonial legacy and a fateful decision made in the waning days of World War II.

After Japan seized the region on a pretext in 1931, China’s Northeast became a key cog in the country’s imperial aspirations — a new industrial and agricultural heartland that would help cement it as a global power.

But new factories and farms weren’t the only things the would-be colonizers brought with them. As part of their military occupation, the Imperial Japanese Army set up several covert biological and chemical weapons development and testing units in the region.

The most infamous of these, the Harbin-based Unit 731, tested its theories of biological and germ warfare on human subjects — including prisoners, dissidents, and civilians. Roughly 300 kilometers to the northwest, in Qiqihar City, Unit 516 likewise oversaw the development and testing of chemical weapons on locals.

In 1945, as the Japanese imperial project was teetering on the brink of collapse, the country’s military and political leaders began to fear retribution for these and other war crimes they had overseen. While the army hurriedly buried or dumped hundreds of thousands of chemical weapons in rivers, fields, and caves throughout occupied China, Japanese officials, officers, and scientists sought to destroy all record of their existence.

In the almost 75 years since, abandoned chemical weapons (ACWs) have maimed or killed thousands of people nationwide, according to Chinese government estimates. In one northeastern county, a researcher found that locals had been poisoned while doing everything from tilling their fields and collecting wild herbs to hollowing out old artillery shells to use as bells. Li was poisoned in 1974, when the boat he was working on inadvertently dredged up a rusted chemical shell from a riverbed.

But the best-known case of ACW poisoning is the “8/4 Incident.” On Aug. 4, 2003, 44 Qiqihar residents were hospitalized after construction workers unwittingly dug up five barrels of mustard gas that had been buried 60 years previously. One, a scrap metal collector who had pried the barrels’ lids off, died within days.

For the survivors, their ordeals were only just beginning. The effects of mustard gas poisoning are incurable and can grow more complex with time. The victims, many of them from the lower strata of society, have spent years unsuccessfully fighting for compensation in Japanese courts, all while contending with crushing medical bills, as well as ignorance and discrimination at home.

Today, many remain haunted by the ghosts of a war that ended before most of them were even born. They swing between righteous fury at those they view as responsible and grateful appreciation of the tireless advocates — both Chinese and Japanese — who have spent decades championing their cause.

Most of all, they say they want justice. But can they get it in time?

It was early in the morning on Oct. 20, 1974, and the Songhua River was already frozen and covered in snow.

Li Chen wasn’t afraid of the cold. He was 29 years old, an army veteran, and a new father. His slight frame belied his strength — everyone called him “Little Ox.”

After his discharge from the army, Li joined the Heilongjiang Provincial Waterway Bureau in 1968, where he was assigned to be an oiler on a river-dredging craft, the Hongqi 09. The ship was tasked with keeping the Songhua, which flows for 1,400 kilometers across Northeast China to the Russian border, clear of silt and buildup.

Li liked the work. During the Mao era, a government job, even a menial one, was considered an “iron rice bowl” — a ticket to the good life. He had to spend six months out of the year on the river, but he and his crewmates were free to mend nets and go fishing in their spare time, or cook a then-sumptuous meal of soybean sprout soup and steamed buns.

Even aboard, he wasn’t completely cut off from home. Li married Wu Fengqin in 1971, and since her parents lived by the river, he could occasionally snatch glimpses of their house from the Hongqi’s deck.

That morning, however, he was distracted from his usual duties by a loud clanging coming from below deck — something had gotten caught in the mud pump and cracked it. A mixture of silt and water leaked into the room where Li and engineer Xiao Qingwu were standing. He still remembers them shouting: “There’s something iron in there!”

When they managed to extract the mysterious object, they saw it was an old artillery shell. Broken on one end, it was oozing a black, oily liquid.

The smell of roasted garlic started to fill the room. Within a few seconds, Li had tears streaming down his face. Then his body started to swell, and he broke out into purple-red blisters, which leaked a yellow slime when they burst.

Before it was over, 35 of the boat’s crew members reported symptoms ranging from difficulty breathing to vomiting bile. At first, no one knew what had happened. It was only a day later that doctors told Li his ship had dredged up an abandoned chemical weapon. The compound he was exposed to was a mixture of mustard gas and lewisite gas. Fatal in high doses, even in lower concentrations it can cause irritation, respiratory distress, and severe blistering.

It is impossible to determine how many ACWs were left in China after the Japanese surrender. To conceal evidence of its war crimes, the Japanese government and military systematically destroyed almost all documents from the war years. In 2003, a state archivist estimated that as much as 70% of the army’s wartime records had been burned or destroyed.

Although there is no authoritative tally, in 1992 the Chinese delegation to the international Conference on Disarmament estimated there were still roughly 2 million undestroyed chemical munitions and 100 tons of raw materials on Chinese soil. Japanese government estimates put the number of left-behind weapons at about 700,000.

Li says he’s lucky to still be alive. He was rushed to a hospital in the nearby city of Jiamusi, then a top medical institution in Harbin, and finally to an army clinic in the industrial center of Shenyang over 500 kilometers away in Liaoning province. Medical records show he suffered “second-degree mustard gas burns on 90% of his hands and forearms, with severe damage to his interdigital folds and the backs of his hands.”

Xiao, the engineer with him that day, was less fortunate. Although he survived the initial exposure, he died July 20, 1991. A court later ruled his death was caused by complications from mustard gas exposure.

Gao Ming was 8 years old when she was poisoned.

In the early hours of Aug. 4, 2003, construction workers in Qiqihar City inadvertently dug up five rusty metal barrels containing leftover chemical agents. Unaware of the barrels’ contents, they sold them on to a scrap metal collector, while nearby residents carried away the surrounding soil for use in landscaping projects.

In cases of mustard gas exposure, the onset of symptoms is not always immediate. For almost two days, the poison leeched outward as the still-unidentified barrels passed through the city’s informal recycling sector and doctors puzzled over a sudden rash of unexplained illnesses.

By the time the authorities realized what was going on and got the problem under control, 44 residents had been exposed.

Gao came into contact with the toxin while playing in a dirt pile outside her neighbor’s house. Within hours, her feet had turned purple and swelled up like eggplants. The youngest of the 8/4 Incident’s victims, she would spend roughly a month in the hospital.

The culprit, “mustard gas,” is technically a misnomer — in military use, it is typically dispersed as a liquid mist. Also known as sulfur mustard, it penetrates most types of clothing, and on contact can cause anything from severe, agonizing blistering and respiratory distress to eye injury, burns, and in high concentrations, death. A known carcinogen and mutagen, a few seconds of exposure can have lifelong ramifications.

But sometimes the deepest wounds are psychological. Despite widespread domestic media coverage of ACW cases beginning in the 1990s, the real causes and risks of chemical poisoning remained poorly understood among the Chinese public. Instead of being hailed as survivors, or even pitied as victims, those poisoned often returned from the hospital to face fear and discrimination.

“The other parents told me that if Gao Ming went to school, then their children would leave,” says Chen Shuxia, Gao’s mother. Gao remembers sitting quietly in the corridor next to the principal’s office while the adults inside debated her future. Still unable to walk, all she could do was stare at the floor and listen.

Her peers could be equally cold. “When I was in school, my classmates kept their distance from me,” she says. “They didn’t play with me. They didn’t talk to me.”

Within months, Gao told her parents she wanted to leave Qiqihar. “I couldn’t stay any longer,” she says. They hit the road before sunrise and headed to Chen’s parents’ home in Xiaobei Village nearly 30 kilometers away.

At her new school, Gao’s biggest fear was being called on to answer a question. In Qiqihar, she had been at the top of her class, but she says she began experiencing memory problems after she was poisoned.

She also remained deeply insecure about her physical appearance. No matter how hard she washed, she couldn’t scrub the smoke-black scars off her feet. Sometimes, when she had the house to herself, she would close all the doors and windows and just start screaming. It wasn’t until junior high school, when one of her teachers made a point of telling the other students her condition wasn’t contagious, that she finally began to relax.

Once, a boy she liked came to visit her at home. She remembers listening as he opened up about his home life: how his dad was ill and his older brother wasn’t able to find a job. Then, slowly, she began to talk about her own past. When she was finished, the boy didn’t pry; he just said: “You suffered a lot as a kid, didn’t you?”

It was as if a huge weight had been lifted from her shoulders.

Li Chen, the former boatman, stayed two months at the hospital in Shenyang before being transferred to an army hospital in Beijing, where he spent most of the first half of 1975.

While there, the staff showed him the effects of mustard gas poisoning by applying it to several live rabbits in a cage. He watched in horror as their fur fell out, their skin began to blister, and they died, one by one.

That was the moment he lost all hope, he says.

Test results for 8/4 Incident victim Chen Rongxi's eyeball, which lost sight following the incident. Courtesy of Chen Rongxi.

According to Osamu Isono, a neurologist at the Kyoto Min-iren Chuo Hospital who has worked extensively with Chinese ACW victims, there is no effective antidote for mustard gas exposure. Doctors can try to minimize the patient’s symptoms and pain, he says, but they will continue to suffer complications throughout their lives.

Since 2010, Osamu has been one of a small group of Japanese doctors who have offered their services free of charge to Chinese ACW survivors, mostly in the form of yearly checkups. “When I met them, many were in extreme pain from their conditions,” he said via email. “There were (cases of) facial and skin lesions, accompanied by respiratory problems, trouble swallowing, and elevated heart rates.”

For the first few years after he was poisoned, Li’s injuries flared up any time the weather changed — a fairly common occurrence in northern China. Every morning he would dip his hands in water and pry apart his badly blistered upper and lower lips. His fingers were webbed together by scars; even if the doctors separated them, they would fuse together again.

“Do you know how many surgeries it took for his hands to even look like this?” asks his wife, Wu. She says she would pretend not to notice as sticky pus oozed from his sores and slowly soaked through their sheets.

With Li unable to work, and his pension stuck for years at an annual payment of just 50 yuan (then roughly $33) — Li’s salary at the time of the incident — it was up to her to keep their family afloat. During the day, she would take their children outside to scavenge for coal scraps; at night, she’d return to empty her husband’s chamber pot, change his dressings, and wipe him down.

Once, Wu walked in to find Li drinking a mix of grain alcohol and insecticide. After the couple returned home from the emergency room, they sat down together. “Maybe it’s better if you find another way out,” Li said to her. Wu just smiled. “This family wouldn’t be complete without you,” she replied.

After years of surgeries and hospitalizations, Li’s condition gradually stabilized. The lesions on his skin slowly healed, and the skin on his hands stopped fusing together. But he remains frail, and his health issues have been compounded by the effects of aging: He is a diabetic and had to undergo coronary bypass surgery in 2004.

According to Osamu, many of those poisoned by ACWs have experienced a similar progression. “In the first few years, many patients were still relatively hale,” he wrote. “Some victims were poisoned as children, but now they’re over 50 years old, and different symptoms are emerging.”

The mounting physical and emotional costs of treatment place a heavy burden on victims’ family members.

Xu Zhifu, 61, was a security guard at a chemical factory in 2003. On the night of Aug. 5, he got a call from his boss telling him the police were dropping off several barrels and that he should look after them. No one told him what they contained, however, and when they arrived he gave them a couple tentative kicks.

By midnight, his skin was itching. Then his legs, chest, and eyes began to bleed.

Today, his vision is getting progressively worse. His world is black and gray, he says; his son and daughter-in-law are simply silhouettes.

Xu’s son, Xu Tiannan, returned to Qiqihar with his wife in 2018. After testing into university in Shanghai in 2008, the younger Xu studied international trade before settling down in the coastal megacity. “I wanted to make a bit more money for my family and still have enough (left over) to get the things I liked,” he says.

But he decided to move back home after his father’s condition worsened. He makes much less money in Qiqihar, but after work he can help his mother care for his father.

“I used to have a lot of ideas, big dreams,” the younger Xu says. “Now? Not so much. For now, my greatest wish is to take good care of my parents.”

“The pain caused by Japan goes beyond just one generation,” he adds. “It can linger for two generations, three generations. When the first generation suffers like this, the next generation has to take responsibility for them.”

Xu Zhifu hates that he’s become a burden on his son. “I have held him back,” he sighs.

Xu Zhifu’s wife, Li Hong, is blunt. “He (our son) said if he didn’t (return from Shanghai), then he wouldn’t be able to see his father,” she recalls. “I said, ‘What does it matter if you see him or not? His life has been miserable. What’s seeing him going to do?’”

The postwar Japanese state has consistently argued it bears no responsibility for compensating the victims of its wartime actions. Nevertheless, in the aftermath of the 8/4 Incident, the Japanese government in lieu of compensation issued a formal apology and paid 300 million yen (then roughly $2.7 million) for both cleanup costs and a victims’ “solidarity fund.”

But many victims quickly burned through their shares of this money paying for treatment. Most of those poisoned during the 8/4 Incident, including Xu Zhifu and Gao Ming, were from the urban underclass: scrap pickers, construction workers, and members of China’s so-called floating population of rural-to-urban migrants. Few had access to urban welfare programs or health insurance.

Yang Shumao had a successful business selling roasted nuts when the 8/4 Incident occurred. The then-39-year-old was poisoned while gathering some dirt from the work site where the toxic barrels were uncovered to build a new roastery.

After he was discharged from the hospital, his old customers gave him a wide berth. “I couldn’t sell so much as half a kilogram,” he says. “People feared the poison was contagious.”

“They called me ‘Mustard Gas,’” Yang remembers.

Yang’s business went bankrupt, and he was faced with a mounting pile of medical bills. He says that over the years, he has experienced symptoms ranging from colds and fevers to liver problems, muscle weakness, and light sensitivity.

Lacking an urban household registration, he’s insured only through China’s New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme, which was founded in 2003 to help plug the holes in the country’s rural safety net. This only reimburses 30% to 40% of his expenditures, however, and doesn’t cover many necessary procedures and treatments.

A typical hospital visit can cost Yang anywhere from 100 to 300 yuan (roughly $14 to $43) — or 3,000 to 5,000 yuan if he has to be admitted. “At first I still had money, and I was hospitalized six or seven times,” he says. “Later I became poor and couldn’t afford to stay in the hospital anymore. Nowadays, I just take some painkillers when it starts to hurt.”

For some, the Japanese solidarity fund itself proved a poisoned chalice. In 2012, an anonymous victim complained that survivors were falling through the cracks of the system. “You (reporters) tell us to go to the government and register for disability, but our arms aren’t broken, our legs aren’t broken. How are we supposed to get a disability certificate?” they told a journalist.

“As for social insurance, there’s no way to certify it. They (the bureaucrats) all say, ‘The Japanese government gave you money.’ They think that’s enough to live on. Even if you explain to them how much treatment costs, they don’t believe you.”

Although Japan’s government has remained obdurate, a number of Japanese civil society groups have sought to help meet the needs of ACW victims.

Since 2006, Japanese defense lawyers, often working through the Japanese nongovernmental organization Society to Support the Demands of China War Victims, have organized physical examinations and raised funds to pay for the treatment of ACW survivors. Osamu, the Kyoto-based doctor, is one such volunteer.

And in 2015, Chinese entrepreneur Wang Xinyue gave 500,000 yuan to the China Foundation for Human Rights Development to set up the Chemical Weapons Victims Relief Fund. That same year, the CFHRD joined a group of Japanese lawyers to establish the “Chemical Weapons Victims Support — Japan-China Future Peace Fund,” which also organizes medical checkups and treatment for survivors.

But as the years pass, it’s become increasingly difficult for advocates to raise funds, according to Osamu. And even at the best of times, these subsidies have still been but a drop in the ocean.

“The first thing is to provide medical assistance and to ensure the victims receive clinical treatment,” says Ohtani Takeo, a history teacher and prominent member of a Japanese organization devoted to supporting victims of Japan’s invasion of China. “Of course, we can’t cover all their medical costs, but many need our continued help. That is the important thing.”

Before his children got married, Yang worried his litany of medical problems would scare off potential in-laws. He opted to keep a low profile — barely appearing, even at their weddings. His kids sometimes send him money, he says, but none of them have told their significant others about what happened to him.

“A mustard gas family, a mustard gas father,” he sighs. “Can any amount of money fill that hole?”

The Japanese government’s unwillingness to pay compensation to the victims of its ACWs is partly because it considers the matter already settled.

On Sept. 29, 1972, the People’s Republic of China and Japan signed a joint communique normalizing diplomatic relations. As part of the negotiations, the PRC formally renounced its demands for war reparations. And although activists in both countries have argued the communique doesn’t necessarily preclude individual victims from filing for compensation, the Japanese courts have been reluctant to challenge their government’s stance on the issue.

But that hasn’t stopped people from trying. Beginning in 1996, a coalition of roughly 300 Japanese lawyers began reaching out to ACW victims and offering to represent them pro bono in lawsuits to try and win compensation from the Japanese government.

Luo Lijuan got involved in ACW litigation two years later, in 1998. Then a young lawyer, she agreed to help represent Li Chen, the boatman poisoned in 1974, and 12 others in a class-action suit filed on their behalf by a group of Japanese litigators.

Luo was astonished that so many Japanese would be willing to fight for ACW survivors. “The way they (the Japanese lawyers) saw it, they were bringing justice for the victims, as well as helping their country by righting a wrong,” Luo says. “They thought (their government) was going the wrong way and had gone too far.”

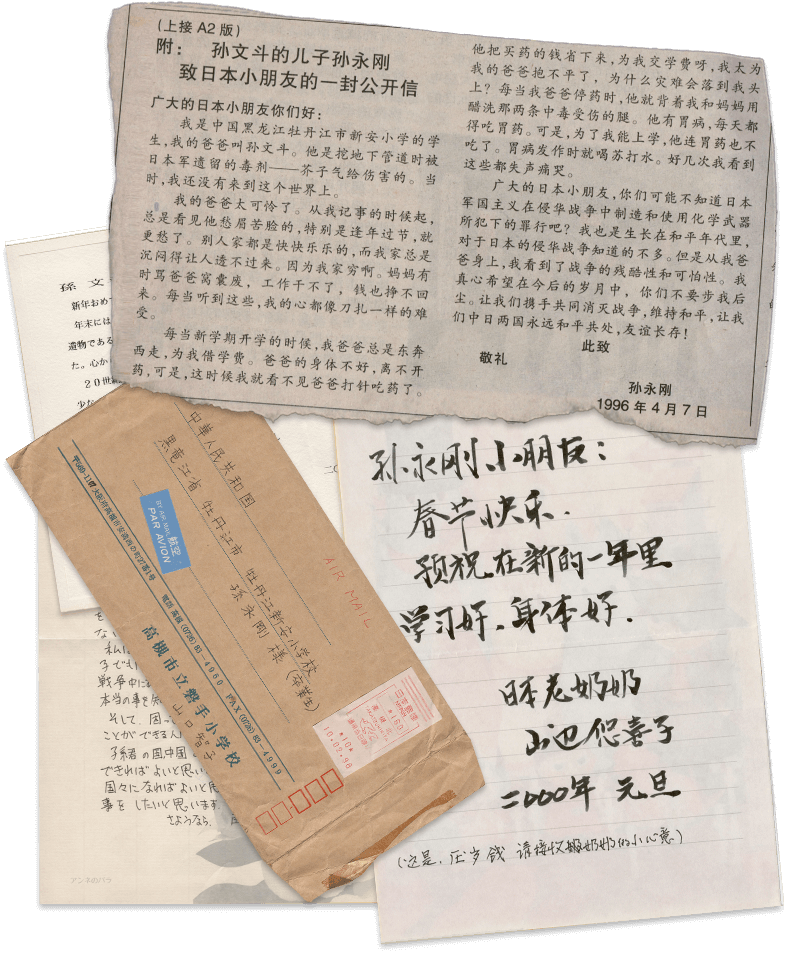

Letters exchanged between an anti-war Japanese activist and Sun Yonggang, whose father was poisoned in the 8/4 Incident. Courtesy of Sun Wendou.

Luo would spend over a decade working with the Japanese legal team to shuttle Li and other victims between the two countries so they could take part in the trial.

Li remembers sitting in the plaintiff’s seat in a Tokyo courthouse on Sept. 29, 2003, as the judge, Yoshihiro Katayama, entered, smiled at him, and read the court’s decision. In an instant, the lawyers around him were pounding their desks and the backs of their chairs; others began kneeling and kowtowing.

Li doesn’t understand Japanese, but he instinctively knew it could only mean one thing: vindication.

The verdict was clear: The Japanese government would be required to pay 190 million yen to the 13 Chinese victims or their surviving kin. Although the judge acknowledged Japan’s official stance that the country was not liable for its actions during the war, he declared that its continued failure to clean up its ACWs was not a wartime act, and therefore not exempted from reparations by the joint communique.

It was a landmark ruling. The verdict caused a sensation in Japan. But within two hours, the Japanese government announced it would appeal.

Li remembers that, too.

Although his skin ulcers had improved over the years, Li says he had been growing progressively weaker around that time. One of his Japanese lawyers implored him to hold on. “Without you, we’ll lose a witness,” he remembers being told.

He started eating better. Before, he’d occasionally complain about taking his medicine, but now he was buying it in bulk. He almost never refused an opportunity to appear in court. “I need to look after myself. I still have a task to complete,” his wife remembers him saying

ACW survivors ultimately filed a total of four class-action suits in Japanese courts, including one by the victims of the 8/4 Incident.

Xu Zhifu was one of their representatives in the initial trial. Wearing a suit and sporting a new haircut, he showed up to court and passed out small posters printed with the character fu — a traditional Chinese blessing — and flower-print handkerchiefs to his Japanese legal team and supporters.

In 2007, however, the Tokyo High Court overturned the lower court’s ruling that favored Li and his fellow plaintiffs. The victims appealed, but on May 26, 2009, the Supreme Court of Japan refused to hear their case. The other three class action suits, including Xu’s, likewise failed.

After his lawyers called and explained the court’s decision, Li lay in his bed and didn’t speak for a whole day.

When overturning the initial judgment that favored Li and his fellow plaintiffs, the Tokyo High Court acknowledged that the victims had been harmed by Japanese ACWs but said there was no way to verify that the injuries had been caused by the Japanese government’s failure to provide accurate information on the locations of its weapon dumps.

According to Luo, the lawyer, the Japanese courts also question whether their government could have feasibly taken action to address the problem of ACWs, given that they were left in Chinese territory.

In 1997, the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) — the most significant treaty ever signed on the manufacture, stockpiling, and destruction of chemical weapons — came into force. Administered by the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, it stipulates that all signatories have a duty to destroy any chemical weapons they abandoned on the territory of another signatory.

During negotiations, China had fought hard to include this provision, seeing it as a way to force Japan to finally take responsibility for its ACWs.

For decades, the postwar Japanese government had refused to acknowledge its use of chemical weapons during WWII. It was only in 1995, after the United States declassified the interrogation records of wartime Japanese officials — which included admissions of chemical weapon use — that then-Japanese Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama finally issued a formal apology.

However, it wasn’t until July 1999 that China and Japan signed a memorandum specifying that, pursuant to the CWC, Japan would provide all necessary funds, technologies, experts, facilities, and other resources for the destruction of Japanese ACWs on Chinese soil. In 2000, the first full year after Japan agreed to fund cleanup efforts, it budgeted $30 million for the task. Some estimates have pegged the overall cost of disposal work at as much as $9 billion.

So far, ACWs have been uncovered everywhere from the Russian border all the way to Panyu District in the southern province of Guangdong. But the vast majority were concentrated in Northeast China.

Dunhua County, in China’s northeastern Jilin province, has possibly the highest concentration of ACWs in the country. As the war wound down and its enemies closed in, the Japanese army planned to make a final stand in the county’s rugged, mountainous terrain. Vast quantities of munitions and equipment, including hundreds of thousands of chemical weapons, were positioned for a battle that never came.

According to a local researcher’s estimate, these ACWs have killed over 1,000 Dunhua residents since the end of the war. Many were exposed in the early 1950s, when Dunhua officials mobilized residents to dispose of the troublesome munitions outside Ha’erbaling Village, deep in the nearby mountains.

Over 60 years later, this decision greatly complicated bilateral efforts to recover and dispose of the estimated 330,000 chemical weapons in Ha’erbaling. After the memorandum was reached, it took years for the Chinese side to build the mountain roads needed to reach the dump sites.

Today, Ha’erbaling is home to the largest permanent ACW disposal facility in China. It operates alongside a mobile disposal facility that has been set up at different times in major cities like Nanjing, Wuhan, and Harbin.

According to official Japanese statistics, as of late 2017, the two sides had recovered over 62,000 ACWs, with the pace of work picking up after 2014. But this is still only a fraction of the total. The original deadline set by the CWC was 2007; China and Japan later agreed to extend this to 2012, and then again to 2022. With just two years left, it remains to be seen whether another extension will be necessary.

Each year, the survivors of the 8/4 Incident gather together for an annual checkup. Organized by a Sino-Japanese nonprofit NGO, it’s a chance to reconnect, catch up, and see who’s still alive.

The first of Xu Zhifu’s fellow patients to die was Li Guizhen. The scrap metal collector had been splashed with chemical residue while prying the lids off the contaminated barrels. Admitted to the hospital with blisters on 95% of his body, he died two days later. “He no longer looked human,” Xu remembers.

And then there was Qu Zhongcheng. Xu and Qu got along well at the hospital, with Xu eventually coming to think of the man as a younger brother of sorts.

Qu died of liver cancer in 2011. Now, with his health failing, Xu wonders if he'll be the topic of conversation at this year’s checkup.

For Yang, too, the checkups are bittersweet. His neighbors have long shunned him, and he keeps his distance even from family. “My wife doesn’t take care of me,” he says. “I don’t blame her. What’s the use of blaming her? It’s not her fault this happened to me.”

So his fellow victims are among the only people with whom he regularly connects. He says that chatting with them in person, going out for a big dinner, and collecting his share of the fund’s donations each year are his “only hopes” in life.

But Yang also knows the clock is ticking. “Many of the victims have already passed away,” he says. “Now Xu Zhifu is like this … How can you not feel afraid? You don’t know who will be next.”

Gao Ming shares his concern. As the 8/4 Incident’s youngest victim, she’s watched as their numbers have dwindled slowly over the years — and worries about what that means for her own future. “I’m terrified that my home life and my body will wind up like the rest of them,” she says.

Since last May, Gao has been in a long-distance relationship with a boy she met in Harbin. Sometimes she fantasizes about what her life would be like if they were to get married — she’d move to Harbin with him, they’d buy a house for her mother, and they’d start a family.

There’s just one catch. “His family doesn’t know about my condition,” she says. “He told me he doesn’t mind, but that doesn’t mean his family feels the same. Some things are depressing to think about.”

These days, Li Chen prefers not to dwell on his injuries.

A decade after Japan’s Supreme Court refused to hear his appeal, he still keeps his photos and court materials from that time stored neatly in a red drawstring bag. Inside are relics from 45 years of pain and suffering, but also joy. A dark blue photo album is filled with pictures of the Japanese lawyers and supporters who worked on his case over the years. In the photos, Li is flashing a genuine smile.

In 2004, Japanese filmmaker Tomoko Kana visited Li to shoot a documentary on the lives of ACW victims. After she had finished shooting, she gave him 500 yuan as “consolation” money. He was touched. After years of fighting in court, he saw it as a gesture of reconciliation from the Japanese side.

Nowadays, Li spends most of his time living in a hospital in Harbin. His pension, finally adjusted, pays him 3,500 yuan a month, about as much as his wife and daughters earn combined. Now he’s the breadwinner. “If I go, this whole family is done for,” he murmurs. His hospital-assigned roommate responds by teasing him for spending every day in bed; his wife just sighs.

In the evenings, Li likes to get out of the hospital and make his way to the banks of the Songhua — the same river he used to sail — and watch the locals fish. He beams whenever someone catches a carp.

“I feel less hopeless than before,” Li says. “I can get by. Be happy for a day; live for another day.”

- WRITERHuang Jijie|STORY EDITORSHuang Fang, Peng Wei, Kilian O’Donnell, and Yang Xiaozhou|TRANSLATORDavid Ball

- DIRECTORTang Xiaolan|PRODUCERYang Shenlai

- CINEMATOGRAPHERSWu Zixi and Tang Xiaolan|VIDEO EDITORSXu Wan and Tang Xiaolan

- PHOTOGRAPHERShi Yangkun|PHOTO EDITORZong Chen

- DATA EDITORZou Manyun|COLORISTJiang Yong

- WEB DESIGNERFu Xiaofan|GRAPHIC DESIGNERSWang Yasai, Long Hui, Zhang Zehong, and Zhang Zhiqiang

- COPY EDITORHannah Lund|PRODUCT MANAGERLü Yan|WEB DEVELOPERKong Jiaxing