Yichun, Heilongjiang province

In the south of Yichun, a city in northeastern China’s Heilongjiang province, is a memorial hall named after one of the town’s most well-known former residents, Ma Yongshun. Next to the building sits a dark red tractor, made in Harbin, the provincial capital of Heilongjiang, that was once a cog in an army of machines that turned the local boreal forests into the timber that made Yichun a boomtown.

Now, the tractor lies disused on the roadside, a scene repeated in cities and towns dotting this vast, empty landscape. The American-Canadian author Jane Jacobs once wrote that while cities shape the countryside, they eventually exhaust the very resources they were built to exploit. This is the fate that has befallen Yichun: a city now bereft of all that defines a city.

Yichun is known nationally as China’s largest “forest city.” In this remote and sparsely populated corner of the country, the municipal government offices in the city center practically look onto the densely wooded mountains that surround it.

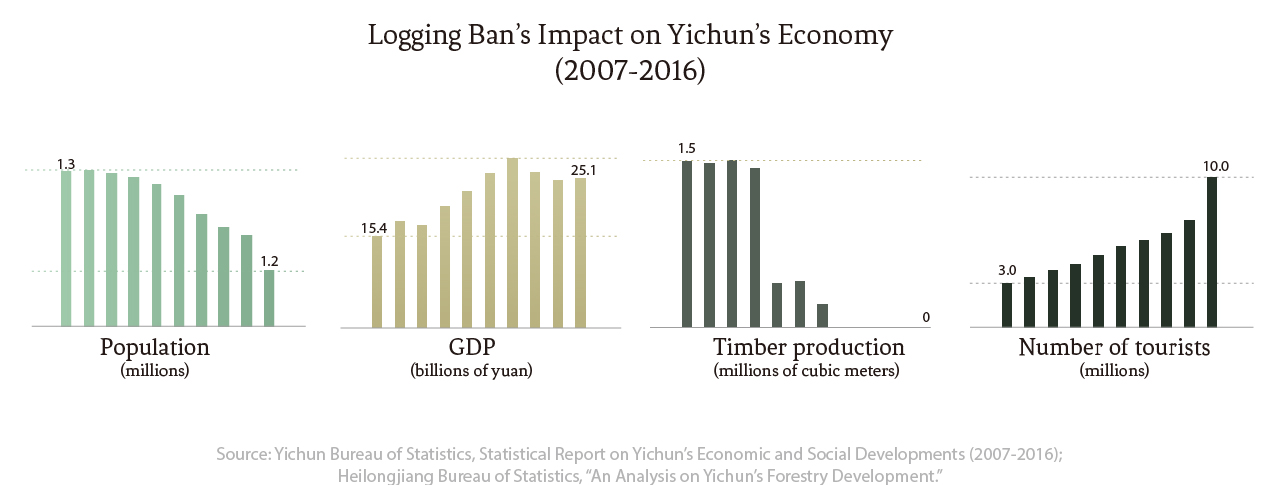

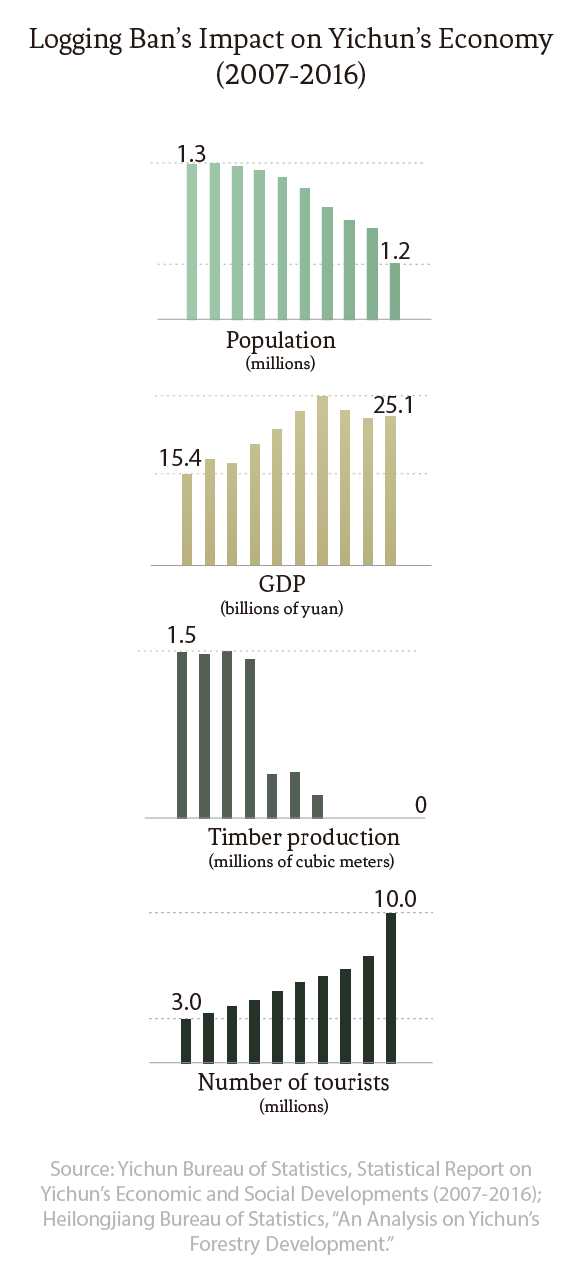

Yichun’s development into a city began in the 1950s, as a product of the region’s booming lumber industry. In the seven decades since, the area has supplied the nation with 240 million cubic meters of high-quality lumber and contributed more than 30 billion yuan ($4.6 billion) in taxes and funds earmarked for forestry projects. Yet even the most abundant resources can dry up. In 2008, Yichun was among the first to be included on a national list of cities that had exhausted their natural resources.

They closed off the mountains to protect them, but we can’t plant anything in these parts. Everyone has left. - Local taxi driver

Over the past three years, Yichun has gone from reducing the amount of logging in its environs to banning the practice altogether. These decisions, in turn, have led to a dramatic decline in population. Yichun had 1.25 million registered residents in 2012 and 1.1 million in 2016, a population decrease of around 12 percent in just four years. But the impact on the local economy is not accurately reflected in the official statistics: The large numbers of homegrown workers who temporarily migrate to larger cities for work have nearly decimated the city’s industry.

Although Yichun is transitioning away from logging and toward ecotourism, it is often paralyzed by the latter industry’s growing pains. The uncomfortable transition makes Yichun a classic case of deurbanization in China.

-

Bare shrubs outside a church in Yichun are decorated with colorful ornaments.

-

By 3 o’clock, the sun has already begun to set in Yichun.

-

The city of Yichun is surrounded by sparsely wooded hills and mountains.

In 2006, Yichun New City, a planned district located across the river from the old city center, was opened for development. On a visit there this fall, I found the roads and skyscrapers even quieter and more lifeless than the nearby pine forests.

As is the case with many new urban districts in China, local government departments were the first to move into the New City, including administrative buildings and the procuratorate, followed closely by the local bank branches.

Architecture in the New City leans toward the monumental: There is a vast new sports complex that towers over passersby, complete with a sizeable soccer stadium. But nobody lives here. There is no rush hour or nightlife to speak of. The broad, six-lane roads lie empty, except for the occasional car or tractor. Red decorative Chinese knots hang from the light posts lining the streets. The sidewalks are spotless, the trash cans largely unused.

Gaudy villas in Yichun New City stand empty, with few people choosing to live in them.

My room was in a large, partly refurbished hotel not far from the stadium, with a full view of the soccer field. In 2014, Yichun hosted the Heilongjiang Provincial Games, and many of the event’s high-profile guests stayed in this building. Only two attendants were on duty, however, when I checked in.

Since autumn of 2015, the stadium’s ground-level shopping center has been home to the Yichun E-Commerce Industry Mall. Almost every storefront is boarded-up, including those belonging to state-owned enterprises like China Post and China Mobile. Just outside the stadium’s gate, a father idly kicks a ball around with his young son. An actual soccer match is taking place inside, and the sound of the referee’s whistle reverberates through the still air.

Northeastern China has all sorts of natural advantages when it comes to winter events. Not only does the climate provide abundant ice and snow, but the region’s expansive area and small population also make it great for ice-skating.

In winter, perhaps as a result of the return of the city’s migrant labor population for the holidays, or perhaps due to the omnipresent sound of people trudging through the snow, you can almost — but not quite — convince yourself that Yichun isn’t as desolate as it seems. The river running through the city freezes over to become a place where families can take their kids for light shows and theme park rides.

A traditional Chinese arch and a dragon boat are surrounded by snow in Yichun.

The older part of town is a little livelier. The commercial district boasts a pedestrian street known, albeit somewhat optimistically these days, as “Prosperity Street.” Built in a vaguely Russian style, it looks more like an upscale farmer’s market than anything else. Milk tea stands, so ubiquitous along pedestrian streets in other major Chinese cities, are few and far between. There’s a Xinhua Bookstore, a clothing store, and a hardware store. The most popular spots on the street are a restaurant specializing in malatang — a mouth-numbing Sichuanese hot pot soup — and a pulled-noodle joint. A few impromptu roadside stands are visible, where vendors hawk cheap bedsheets or fruit from baskets on their bikes.

Time moves at its own pace here. By 3 o’clock in the afternoon, the day is fading to dusk, and residents leave work at 4:30 p.m. An hour later, the malls close. Half past 6 here feels like midnight anywhere else in China.

In warmer months, however, older residents will go out at night and dance in public squares. Prosperity Street and the park by the river are both home to large dance troupes, a source of vitality in this sprawling but nearly empty city. Sometimes assembling in a square formation, other times into long, snaking lines, the elderly dancers are always happy to share the city’s massive public spaces with each other.

Most travelers to Yichun pass through the city on their way to the nearby mountains. The road north leads them through numerous natural parks showcasing the bleak beauty of northeastern China. In May 2016, President Xi Jinping made an inspection tour of Shangganling, a suburb of Yichun where Xishui National Park is located. This brought the region a much-needed morale boost. Taxi drivers still recall the visit in fawning tones: “Since Uncle Xi came, there have been more tourists,” said one, using an affectionate nickname for China’s leader. “Business is better for us drivers now.”

But business must get better still, or else the taxi drivers, too, may follow other locals out of the city. The further north you go, the fewer people you see. “They closed off the mountains to protect them [from deforestation], but we can’t plant anything in these parts — so everyone has left,” a cab driver told me. In the few years since Yichun banned logging, Shangganling lost a majority of its residents. The area’s population now hovers around 10,000.

-

Yan Su

“I’m a civil servant in Yichun. My girlfriend wants to go work in the south of China, and I think I’ll follow, too, because I love her.”

-

Li Xiao

“My father drives a taxi. I wish he would take me to visit Beijing one day.”

-

Liu Liang

“Maybe there won’t be a ski ground on the college campus, and I’ll rarely get to ski. But still, I’m eager to leave home.”

Yan Su

“I’m a civil servant in Yichun. My girlfriend wants to go work in the south of China, and I think I’ll follow, too, because I love her.”

Li Xiao

“My father drives a taxi. I wish he would take me to visit Beijing one day.”

Ma Yongshun Forestry Town is located in Tieli, a city south of Yichun. Officially, the forestry town is known as a “village for ecotourism” and a “model for the beautification of other forestry center construction projects.” In the 1950s and ’60s, Ma Yongshun was both a model worker in the lumber industry and an avid tree planter — China’s Johnny Appleseed, if you like. A former resident of the area, Ma now has his name emblazoned on the town hall.

Perhaps hoping to capitalize on elderly people searching for summer vacation homes away from the scorching heat, Ma Yongshun Forestry Town officials developed a real estate project known as the Riyue Gorge Scenic Village. Only a few of the homes have found buyers, however, and those tasked with tending to the neighborhood’s yards and lawns spend more time discussing work opportunities in the provincial capital of Harbin.

Looming over the patch of kitschy Italian-style villas is the forestry center, nestled between the trees and high up in the mountains. The offseason here begins as soon as the summer ends. By September, the forestry center is free of tourists, and the employee compound is covered in signs offering rooms for rent.

The bedroom of an apartment lies mostly empty. The owner has been away for two years.Last winter, the popular Chinese television program “Where Are We Going, Dad?” chose Tieli as the location for its season finale. Pieces of the set — clapboard houses hastily thrown together — were left behind in the town after filming finished. Signs declaring “Tian Liang stayed here,” a reference to one of the show’s stars, can still be seen hanging from village doors. Locals enthusiastically retell stories of how the show’s location scouts arrived in the village. Their spare rooms are piled high with discarded props, though it is rare for anyone to come and stay.

The bedroom of an apartment lies mostly empty. The owner has been away for two years.Last winter, the popular Chinese television program “Where Are We Going, Dad?” chose Tieli as the location for its season finale. Pieces of the set — clapboard houses hastily thrown together — were left behind in the town after filming finished. Signs declaring “Tian Liang stayed here,” a reference to one of the show’s stars, can still be seen hanging from village doors. Locals enthusiastically retell stories of how the show’s location scouts arrived in the village. Their spare rooms are piled high with discarded props, though it is rare for anyone to come and stay.

Life in Yichun will never resemble that of any of China’s major metropolises. Here, the mountains are the residents’ only permanent companions. On rainy fall evenings, locals grab their flashlights and head out hunting for the wood frogs that live on the mountainside and provide ingredients for traditional Chinese medicine. Pacing up and down, the hunters look as if searching for something valuable they dropped on the road.

Jiayin, the northernmost town under Yichun’s jurisdiction, lies on the border with Russia. Built on flat ground, the town is still thriving, as the impact of the logging ban was felt less keenly here than elsewhere. The region’s arable land has given locals more options and economic opportunities than in other parts of Yichun.

There are more people on the streets here than to the south, but Jiayin is still largely unpopulated. The town’s small shops are mostly stocked with Russian chocolate, cakes, sausages, and alcohol imported from their vast northern neighbor.

The first fossilized dinosaur found in China was unearthed in Jiayin, and dinosaur-themed lamp posts and trash cans line the city’s streets. There’s also a rarely visited dinosaur amusement park, stocked with huge plastic sauropods nibbling at the trees. Presumably, with so much space available, the park’s designers saw no need to use miniatures.

But Jiayin is merely a small beacon of hope in the great northeastern wilderness. These days, Yichun looks to be going the way of its prehistoric predecessors, a once-great relic of a former age captured as if in amber, existing without purpose in perpetual isolation.

Crows fly over a landfill site.

Plastic trees on a snow-covered frozen lake outside Yichun's government buildings.