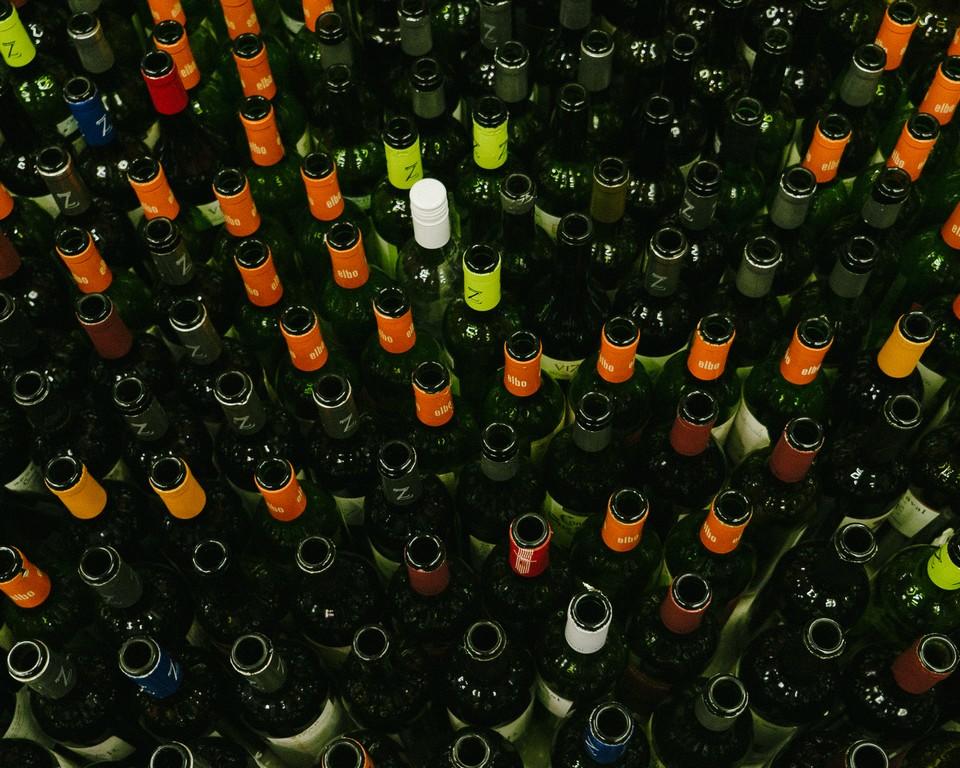

From the hallowed vineyards of Spain’s city of Valladolid, bottles of red wine navigate a long journey toward the increasingly thirsty consumers of China’s middle class. Usually, they go by sea, but an assortment of rail connections — launched in 2011 and heavily promoted under the transcontinental trade initiative, “One Belt, One Road” — has given merchants new routes to and from China.

Huang Jiangjiao, a Chinese entrepreneur who started his red wine business in 2011, now ships about 20 to 30 percent of his bottles by train. “I was looking for a faster way to ship wine from Spain to China, because I sometimes get express orders from clients,” he tells Sixth Tone.

These in-demand boxes of Vizar wine will travel through seven countries, passing the Kazakh-Chinese border, before ultimately reaching China’s eastern city of Yiwu, a place known for its manufacturing and exporting prowess. Much like the rest of the country, Yiwu is eager to build a reputation for importing, too.

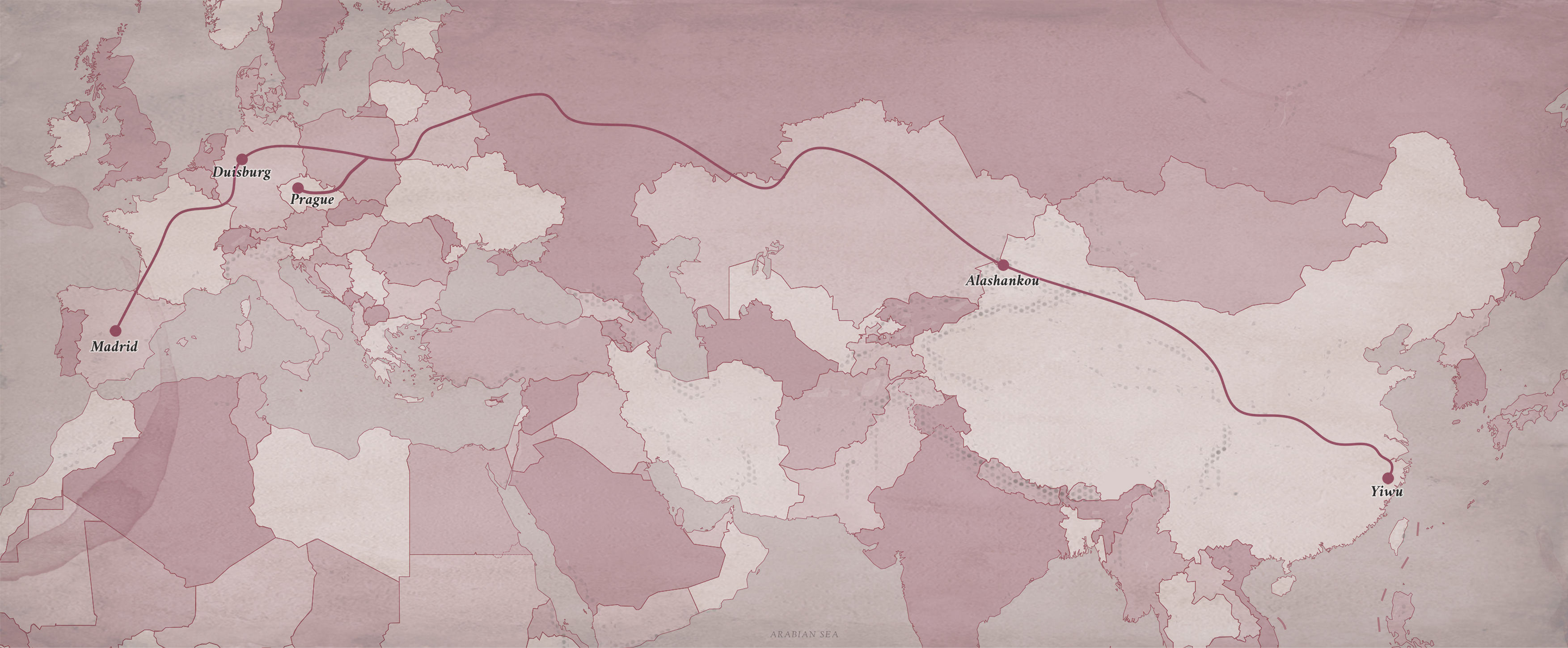

The current 65 rail routes through Eurasia are collectively known as the China Railway Express. They mostly use the same tracks, but service different cities in Europe and China. Yiwu is the starting point for the longest railway connection, which chugs all the way to Madrid. As the train makes its way to and from Spain, the containers have to be hoisted onto new wheels three times because of differing track-widths between the seven countries.

Since the Yiwu-Madrid route launched, there have been 412 outbound trips to Spain, and only 105 trips to China, according to Yiwu Timex Industrial Investment Co. Ltd — the company operating all trains between Yiwu and Europe.

China Railway executive Han Xiao claims that train transport is 80 percent cheaper than air and twice as fast as maritime transport. Conversely, however, it is also slower and more expensive, respectively. For wine vendor Huang, only express deliveries make financial sense to send by rail, so he ships the bulk of his inventory by sea. “It’s much cheaper,” he says. Transporting a standard 40-foot container of goods by rail costs $2,500, according to Feng Xubin, CEO of Timex. Ocean freight costs a little over $200 per container.

Nevertheless, there have been over 11,000 China Railway Express trips as of October. Dubbed “the Silk Railroad” after the famed trading routes of yesteryear, the project aims to strengthen trade between China and Europe. To get a closer look, Sixth Tone reporters traveled to Spain, Germany, the Czech Republic, the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, and Yiwu to trace this 21st-century Silk Road.

About three hours north of Madrid is Valladolid, one of Spain’s best-known wine regions. Its arid summers and winters make it ideal for growing grapes. And since China is set to become the world’s second-largest wine consumer by 2020 — according to the International Wine & Spirit Research organization — more of Valladolid’s wines are being exported to China.

Alberto Segovia Viccar, an 87-year-old farmer who has worked in vineyards since he was 13, holds grapes from his own vineyard, located in Toro, a well-known wine region in northwestern Spain.

The Toro area, located in northwestern Spain’s Castilla y León, is dotted with wineries.

Grapes are ripe for harvest in the Castilla y León region. Thanks to its arid summers and harsh winters, the area is ideal for growing grapes.

Wine barrels are stacked in the corner of a warehouse. Today, barrels are rarely used to transport wine. Wine is typically transported long-distance either in bottles or large plastic pouches.

In the town of Tordesillas, women dance in the main square. Some locals say that “Conversation starts with the first glass of wine.”

Winemaker Santiago Enciso, 52, drinks red wine while sitting on his sofa. He was born and raised in Valladolid, and has given himself the Chinese nickname “liu-liu,” which refers to his birth-year, 1966, and the Chinese phrase “everything goes smoothly.”

In Enciso’s office, there’s a map of China and a 10-yuan note. He currently plans to promote his wine for China’s market. Enciso says: “I think China has a power of consumption — [with a] very important middle class and [upper] class. They enjoy wine much more than the other drinks.”

Chen Cui is a postgraduate student at the University of Valladolid. She also works as the head of local sales promotion for a wine company. “I’m new to the wine industry, but my boss is a very patient man who’s taught me a lot about wine,” she says.

“China” is written on a packaged wine box at a company’s warehouse. Winemaker Enciso says: “We believe, at its current rate, China will overtake the European and U.S. markets.”

Chen Cui picks out wine at a bodega, whose history traces back to 1886 in Tordesillas. Tourists from all over the world come to learn about wine’s history and to purchase the best wine.

Packaged wine in a company’s warehouse is ready for delivery to other parts of the world. Transporting wine requires maintaining consistent temperature. China Railway Express uses temperature-controlled containers so that wares don’t spoil when passing through the frigid central Asian steppes.

The first China freight train from Yiwu arrives in Madrid in Dec. 2014. The China Railway Express line from Yiwu to Madrid is the first direct link between China and Spain, and is 13,052 kilometers long, making it longer than the Trans-Siberian Railway and the Orient Express.

Western Germany’s city of Duisburg, located at the confluence of the Rhine and Ruhr rivers, has transformed itself from a declining steel town to a logistics hub. For 80 percent of Chinese trains, Duisburg is the first European stop, according to The Guardian.

On average, around 29 trains arrive at the Duisburg Intermodal Terminal every week, station employee Amelie Erxleben tells Sixth Tone. These trains carry toys and clothes all the way from Yiwu, and return to China with Spanish red wine, British baby formula, and German auto parts.

Landschaftspark Duisburg-Nord is a postindustrial landscape park in Duisburg, and represents the heavy industrial culture in the Ruhr area. The original site used to be a steel mill, which was abandoned in 1985.

A train model on a China Railway Express service provider’s desk in Duisburg. The German city has been seen as the world’s largest inland port. Around 80 percent of freight trains from China now make it their first European stop.

Tourists visit the Chinese Garden in Duisburg Zoo, which was a gift from Duisburg’s twin city of Wuhan in central China. It was built in 1988 using materials imported from China.

Chen Kaifeng, Duisburg’s branch manager for a China Railway Express service provider, poses for a portrait in his office. “The difficult thing about working here is understanding the local culture and laws,” he says. “For example, trucks are not allowed on the road during the weekend, so you have to arrange schedules accordingly.”

A potted plant in the corner of the office. For much of the 20th century, the city of Duisburg was a steel-and-coal town. Now, the city has transformed into a logistics hub.

Yu Kai, the business development manager for GFW Duisburg, poses for a portrait. GFW focuses on economic cooperation with China.

“In 2014, there were only 40 Chinese companies in Duisburg,” she says. “By the end of Dec. 2017, this number had exceeded 100. The local government realized that in order to serve Chinese companies, they needed employees [for better reception], like me.”

Bottle openers on sale at a Duisburg store.

Amelie Erxleben works as a consultant of international business development at Duisburg Intermodal Terminal. She studied Chinese in Xiamen University in 2009, and her Chinese name is “Zhang Ziyi,” which has the same pronunciation as the well-known Chinese actress. “People called Düsseldorf ‘little Japan,’ and now they call Duisburg ‘little China,’” Amelie says.

Containers from China Railway Express are stacked at the Duisburg Intermodal Terminal. In 2014, when Chinese president Xi Jinping made Duisburg one of the few stops on his state visit to Germany, Duisburg’s mayor Sören Link said, “There are signs that the city’s importance will keep growing. We could become China’s gateway to Europe — and vice versa.”

With its advantageous location and lower labor costs, the Czech Republic has become a developing logistics center in central Europe. In July 2017, a freight train carrying 82 containers of Czech products departed from Prague. Sixteen days later, it arrived in Yiwu, delivering crystal glass, beer, and auto parts.

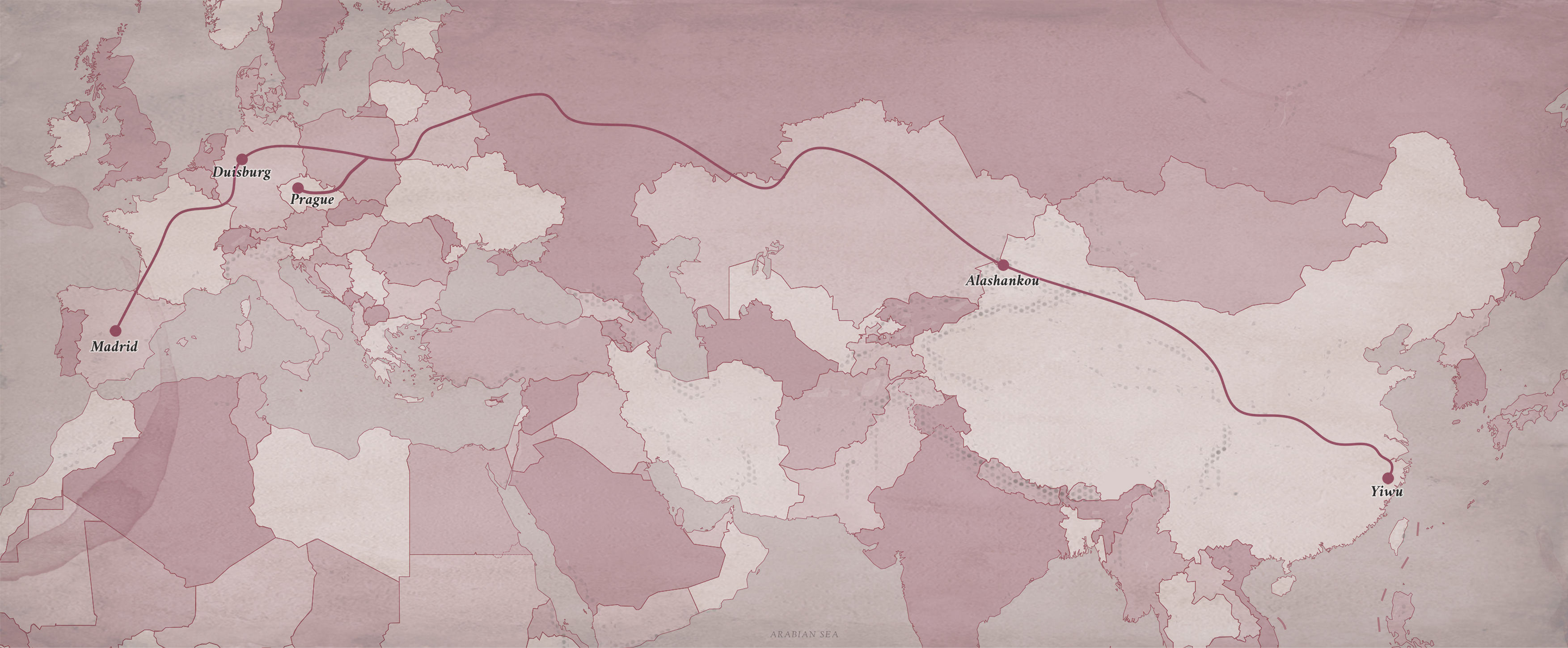

“Crystal glass is high-density, so it’s not meant for air transport,” says Jia Jianping, head of a business association in Prague. “We used to transfer it by sea, but it took longer and was riskier, too, because these products are fragile and highly valuable.” Jia thinks it best to balance cost and time by using rail transport.

Tourists pause in front of a crystal and glass shop on a street in Prague.

A tourist blows bubbles in Prague’s Old Town Square. Situated in the northwest on the Vltava River, Prague is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic.

A bride poses for a photograph on the bank of the Vltava River.

On the west bank of the Vltava River, a couple rests in Kampa Park. Now, with increases in Chinese investments and Czech exports, the Czech Republic has one of the strongest relationships with China among central and eastern European countries.

Li Wei works for a China Railway Express service provider in Prague. Li moved to the Czech Republic with his parents when he was a middle school student in the ’90s. “When I was young, there was only a small group of Chinese people living in the Czech Republic,” he says. “The community has since become much bigger.”

The Lovosice Station, 60 kilometers away from Prague, is one of China Railway Express’ terminal stations. In 2012, China started what came to be called “the 16+1 initiative” in an effort to cooperate with more than a dozen eastern and central European nations.

Crystal cups are displayed on a glass cabinet in a shop in Prague. With the China Railway Express trains, there are more exports to China of Czech crystal, Czech beer, and Škoda-branded automobiles.

So far in 2018, more than 10 million tons of cargo has passed through Alashankou and Khorgos, two trade gateways that border Kazakhstan. (In comparison, the world’s largest shipping port, Shanghai, handles more than 640 million tons of cargo a year.)

Today, many of the houses and lanes in Alashankou are empty. The majority of the 10,000-strong population is made up of migrants from other provinces who have moved to seek jobs as railway workers and cargo handlers.

Zhang Xiafei, who works in customs at the Alashankou Station, moved with his parents from Hebei province 15 years ago. He grew up and went to school in this remote border town and says he’s witnessed its rapid change since the railway border crossing became part of the Eurasia route launched in 2011.

Li Rui, chief dispatcher, was assigned to the Alashankou Station after serving in the military. For years now, he’s only stayed in Alashankou on workdays. In his spare time, he either goes back to his home in Urumqi, Xinjiang’s capital, or to the nearby city of Bole. With cold winds and snowfall starting in October, railway workers don heavy coats as they wait for the trains to come and go.

A family from the nearby Altay region visit the country’s border-crossing spot in Alashankou, Bortala Mongol Autonomous Prefecture.

Located near Central Asia’s Altay Mountains and the Barlyk Mountains in the northwest of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Alashankou has long been an important trade gateway.

Workers repair the rails at the Alashankou Railway Station.

In 1990, in order to bolster trade between inland China and Central Asian countries, China commissioned a railway from provincial capital Urumqi to Alashankou. Since then, according to data published by the Alashankou government, more than 6,000 Chinese and European trains have passed through customs at Alashankou, reaching 13 countries and 36 cities.

Customs officer Zhang Xiafei stands in front of a slide where he used to play as a child in residential Alashankou.

Zhang relocated with his parents from Hebei province and has been living in Alashankou for 15 years. Zhang has witnessed the city’s many changes.

Containers wait to be loaded at a terminal in Alashankou.

More than 100 million tons of cargo have been transported in the past 16 years through Alashankou.

A box to store cellphones inside Alashankou Station’s dispatch control center. Workers are not allowed to use phones during work hours in order to prevent accidents.

A Kazakh man chooses lamb meat at a local market.

A gate for Alashankou’s bonded zone for stockpiling stands unfinished, awaiting further construction. In 2011, the State Council, China’s cabinet, approved it as an important place to attract foreign business and investment.

Dispatch group leader Li Rui poses for a photo in an Alashankou Railway Station meeting room. Li and his colleagues are mostly from Urumqi and have been assigned to Alashankou Station after serving in the military.

In the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, businessmen from Kazakhstan wait by the China-Kazakhstan border gate for a bus to return home.

Four railroad passengers pick out goods at a souvenir shop in Alashankou. Souvenir shop owner Guo Qingping tells Sixth Tone that there used to be only one official shop in Alashankou where people could buy limited imports from Russia, but most of the goods were expensive liquors or cigarettes.

Two Kazakh translators Nazigul (left) and Aida (right) chat in a clothing store in the China-Kazakhstan Khorgos International Border Cooperation Center.

Shops in the trade zone usually hire translators to facilitate transactions and help Chinese businessman communicate with other buyers.

The year’s first snow falls on Sayram Lake in Bole, Bortala Mongol Autonomous Prefecture.

There is stunning scenery on the road from Urumqi to Alashankou and Khorgos. As early as 1989, after the railway line between Khorgos and Zharkent, Kazakhstan opened to other countries, areas around Khorgos became hot spots for both domestic and foreign tourism along the Silk Road.

After three weeks and seven countries, the trains that started their journey in Madrid arrive in Yiwu. The city’s reputation as an export hub comes from its commodity wholesale market, the largest of its kind in the world. Buyers from all over stroll the aisles, where there are signs written in Chinese, English, Korean, Arabic, and more.

The railway port is a coming and going of trucks that drop off commodities to be sent on to Europe. Soon, the yearly exodus of Christmas decorations will fill containers headed west. But the local government hopes to see more trucks coming by to collect items that have been shipped the other way, like Huang’s bottles of red wine. By now, those travel-weary refreshments have been delivered to consumers in eastern China, nearly 10,500 kilometers from their home in Valladolid.

A night view of the freight yard at Yiwu Railway Port. Yiwu is both the starting and ending point of China Railway Express’ Yiwu-Madrid route.

A railway worker does his regular check alongside the tracks in Yiwu West Railway Freight Yard.

One train a week has been Europe-bound since the Yiwu-Madrid route launched.

Customs officers inspect goods at the Yiwu Railway Port.

So far, over 6,600 containers have arrived at the Yiwu Railway Port from returning trains. Most of the merchandise is wine, infant-care products, high-end kitchen utensils, cleaning equipment, and auto parts.

Empty bottles in an imported wine shop at the Yiwu International Trade City.

As wine consumption increases in China, the drink’s variety and long shelf-life is enticing many merchants to join in the wine market. On the trade city’s first floor, several shops specialize in imported wines.

Wine businessman Huang Jiangjiao introduces wine to his clients at the Yiwu International Trade City.

Huang lived in Spain for more than 30 years and started his business there. In 2011, he opened his wine shop in the Yiwu International Trade City after an invitation from the local government in 2009. Now, Huang’s wine business is growing, with sales increasing by at least 20 percent every year.

Customers sample wine at Huang’s shop in the Yiwu International Trade City.

“More and more customers come to us to learn how to properly identify and taste wine,” Huang tells Sixth Tone.

A China Railway Express train model chugs along in the Yiwu International Trade City.