In July, Maotai Town enters the wet season, the red soil washing off the banks of the Chishui River and turning the water brown overnight. Peng Dengyou, a 73-year-old resident, stands by the river, staring down at the fast-flowing current. A retired warehouse manager for a local liquor producer, Peng recalls a childhood spent bathing in the waterway or even drinking from it when thirsty. “This place has gone through a lot of changes,” Peng says. “So has the Chishui River.”

Maotai is a town built on baijiu. In 2016, Renhuai — the city that administers Maotai — produced 330,000 kiloliters of the liquor worth 58.8 billion yuan ($8.9 billion). The potent spirit accounts for a staggering 70 percent of the local government’s annual fiscal revenue.

Distillers say none of this would be possible without water from the Chishui River, which has been dubbed the “river of liquor.” Baijiu is made from fermented sorghum and other grains after rounds of distillation, for which the river water is crucial. “We cannot live without the Chishui River,” Wang Zongde, whose family owns a local baijiu factory, tells Sixth Tone.

When the water returns to its original dark-green hue in October, hundreds of people gather to honor the river and mark the start of a new distilling cycle, placing soil, sorghum, and pig heads by the riverbank as sacrificial offerings. The annual festival is a well-preserved custom always held on the ninth day of the ninth lunar month. But the river is no longer pristine: As mines and factories have sprung up in surrounding areas, and towns have continued to grow, the water quality is deteriorating.

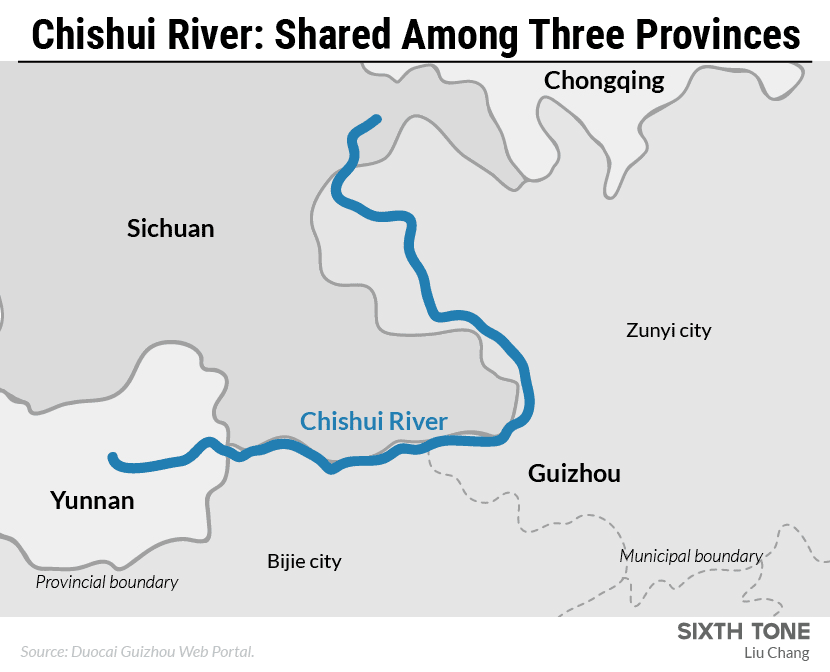

On its journey from a mountainous, remote part of southwestern China’s Yunnan province, the Chishui River snakes more than 400 kilometers through Guizhou and into Sichuan province, where it feeds into the Yangtze, China’s longest river. For centuries, the areas around the river’s middle reaches in Guizhou have used the waterway in baijiu production, allowing them to prosper much faster than neighboring regions.

Development in parts of northeastern Yunnan has started to catch up — with the gross production value of Zhenxiong County, where the river originates, increasing by 470 percent in the last decade — but progress comes at the expense of the area’s natural resources. According to Ren Xiaodong, director of the Community-Based Conservation and Development Research Center at Guizhou Normal University, the upper reaches of the river have pinned their economic hopes on sectors like mining and chemical processing, which can quickly boost the local economy but are often poorly regulated. While environmental protection laws govern wastewater disposal, enforcement is lacking. Even now-defunct sites like the many mines dedicated to pyrite — a mineral known as “fool’s gold” — that used to operate in the area continue to affect the river’s water quality.

The diverse makeup of their economies has put Yunnan, Guizhou, and Sichuan at odds over how the shared river should be used and protected. As the towns along the upper reaches discharge often-untreated industrial wastewater into the river, they threaten those along the lower reaches, whose livelihoods depend on tourism and baijiu production.

This has created a predicament, but Ren believes there are solutions. A decade ago, he came up with a compensation system: Given that a clean river had helped the lower reaches become rich, he thought, paying the upper reaches a fee for constraining development to maintain the water quality seemed only fair.

None of the parties involved were particularly keen on the idea, and Ren lobbied for years without success. But in 2016, the State Council — China’s cabinet — released guidelines governing the establishment of ecological compensation mechanisms and encouraging pilot schemes, effectively bringing the three provinces back to the negotiating table.

A child helps push his father’s ferry away from the riverbank with an iron bar in Maotai Town, Guizhou province, July 17, 2017.

A retired ‘baijiu’ factory worker surnamed Chen rests after a swim in the Chishui River, Maotai Town, Guizhou province, July 14, 2017.

Last year, representatives of each province’s environmental protection bureau met and set up a task force. On Sept. 20, Yunnan, Guizhou, and Sichuan signed an agreement, pledging to implement a joint plan for the ecological protection and economic development of the Chishui River Basin. While the plan includes a natural resource compensation system, the task force hasn’t yet worked out the details, nor has it managed to answer a number of crucial questions: What’s the monetary value of keeping the river clean? How much does Guizhou stand to gain from good water quality, and how much is Yunnan losing out on?

It’s a complicated undertaking, says Zhang Yong, head of the propaganda department at Guizhou’s environmental protection bureau. “Our province has its own opinion, and other provinces are not yet aligned with us,” he explains, adding that the evaluation methods and compensation amount remain problematic, and that the scheme will require assistance from the central government. But in theory, Zhang believes the compensation scheme makes sense. “When the upper reaches send down good-quality water, the lower reaches should compensate them for restraining their industrial development,” he says.

Money could be a powerful incentive for the cash-strapped parts of the Chishui River Basin in Yunnan. Flawed environmental protection facilities — such as shoddy wastewater treatment systems — and a lack of funds for pollution control remain the “prominent problems” for maintaining the Chishui River’s water quality, the Yunnan environmental protection bureau told Sixth Tone in a written statement.

Even if all parties agree on the cost of keeping the river clean, the question of who is to pay remains. Maotai Town and the city of Renhuai, for instance, are relatively wealthy — but Guizhou as a whole is among the poorest provinces in China. The fact that the river runs along the border between Sichuan and Guizhou also makes it difficult to divvy up responsibility, according to the Sichuan environmental protection bureau. “The situation is complicated and unique,” the bureau told Sixth Tone.

-

Boatman Luo Fuqi, 60, sits on his ferry waiting for customers in Maotai Town, Guizhou province, July 17, 2017.

-

A man fishes in the Chishui River, Maotai Town, Guizhou province, July 17, 2017.

-

Locals sit by the side of the Chishui River, Maotai Town, Guizhou province, July 14, 2017.

Yet the plan is not without precedent: Two neighboring Guizhou cities along the Chishui River have agreed on a similar, albeit smaller-scale, compensation scheme.

The city of Bijie is known for its coal, electricity, and tobacco industries, while Zunyi — which administers Renhuai and, thus, Maotai Town — needs clean water for baijiu production. Due to rapid urbanization and relatively poor environmental protection, a huge volume of household and industrial wastewater from Bijie has been discharged into the river, causing conflict between the cities.

In 2014, the two cities agreed that Zunyi would regularly test the water and pay Bijie if the water quality met the agreed-upon standard.

Over roughly two and a half years, Zunyi paid Bijie a total of 28 million yuan, which was put toward environmental protection and ecological conservation efforts — including building wastewater treatment facilities, according to local officials. Bijie has continued to grow over this period, but it has also managed to maintain good water quality.

Ren hopes the agreement can be scaled up and eventually become a model for cross-provincial compensation. But what works for two cities might not be applicable on such a grand scale, Zhang explains, summing up his thoughts in a metaphor: “There are always ways to solve domestic problems,” he says, “but the situation gets complicated outside of your own house.”