Rebuilding

the Wild Great Wall

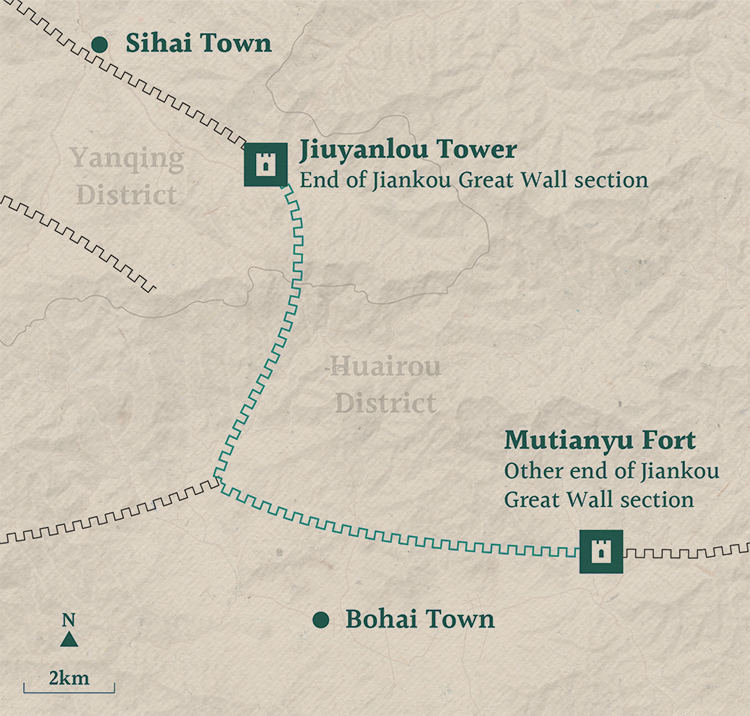

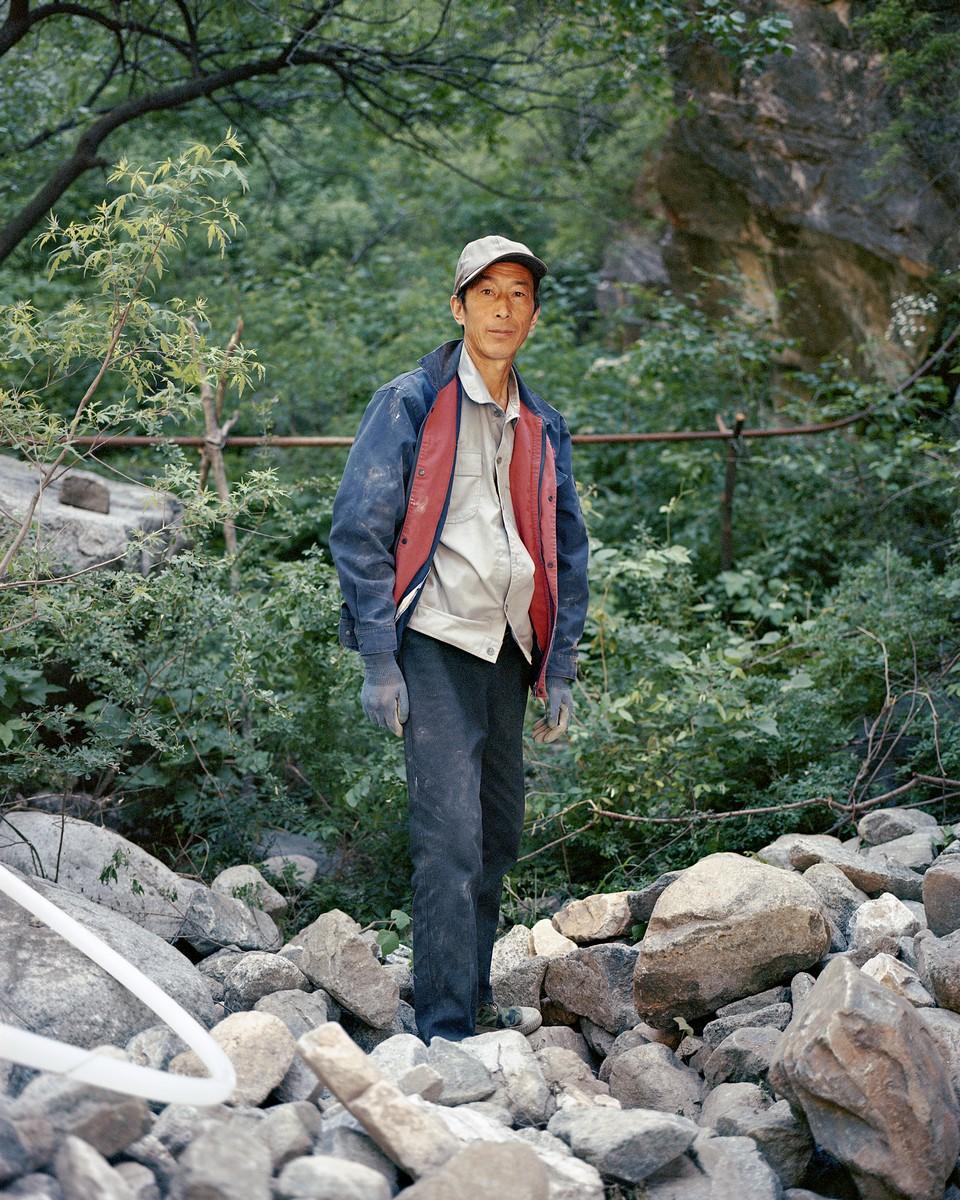

BEIJING — Walking stick in hand, Cheng Yongmao pushes aside a dewy branch as he strides along a crumbling section of stone wall running up a steep hillside.

Hiking in this mountainous area can be punishing, but the 63-year-old is light on his feet. As the chief architectural engineer for the restoration of Jiankou — one of the most precipitous sections of the Great Wall — Cheng spends hours each day climbing the peaks north of Beijing, advising workers on the repairs.

Cheng and his team are part of a massive project to preserve China’s most famous monument, which stretches from China’s eastern coast to the edge of the Gobi Desert more than 2,000 kilometers to the west.

It’s a daunting challenge, made even more difficult by the rough terrain. Along the remote Jiankou section, restorers use mostly traditional materials developed during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) — which they lug to the wall using similarly old-fashioned methods.

Donkeys carry bricks and bags of lime as far as the mountain ridge. Then, workers use pulley systems to lift the objects onto the wall, before carrying them up to the watch towers on their backs.

A view of the Jiankou Great Wall section in Beijing, May 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

“Transportation of materials is one of the hardest parts,” says Cheng. “Only mountaineers can do this work.”

The repairs, however, are urgently needed. The Great Wall was constructed by successive Chinese imperial dynasties spanning nearly 2,000 years — from the third century B.C. to the 17th century A.D. And time has taken its toll on the ancient fortifications. Years of exposure to the harsh northern Chinese climate has weakened many sections, while human activities have damaged the structure even further.

“Only mountaineers can do this work.”

Cheng Yongmao, engineer

In the early years of the People’s Republic of China — when developing the country’s war-torn economy was prioritized above all else — roads, bridges, and railways cut through the wall. Impoverished local villagers, meanwhile, stole bricks to build houses and animal pens.

More recently, the chief danger has been tourism. As China’s economy took off in the 1990s, people across the country began tapping the Great Wall’s potential as a travel destination, but often took few precautions to protect it from the visiting hordes.

At times, the commercial activities went too far. In 2006, the body managing Juyongguan, a section of the Great Wall near Beijing, started allowing visitors to carve their names on the bricks for a 999 yuan ($125) fee as part of a “love wall” program.

In Jiankou, locals installed ladders next to the harder-to-reach stretches and charged hikers to use them. Business was good. More than 100,000 people came to walk the spectacular mountain passes each year.

But here, too, the flood of tourists has caused problems. Lin Jiang, a 48-year-old native of Xizhazi, a village at the foot of Jiankou, tells Sixth Tone traces of the wall’s history have disappeared in recent years.

When Lin was young, he used to hike up to Zhengbeilou — the largest watch tower in the area. On the floor, there was a brick bed where Ming soldiers used to burn wood to keep warm while on duty. Today, however, the bed is long gone.

“From the 1990s, photographers started to come to Jiankou,” says Lin. “During peak times, there’d be over 100 people setting up cameras on Zhengbeilou.”

The constant pounding of feet and walking sticks, meanwhile, has loosened the ancient brickwork, creating safety risks. At “Eagle Flies Facing Upward” — a near-vertical wall climbing a steep peak — in particular, many hikers have been injured and even killed after losing their footing.

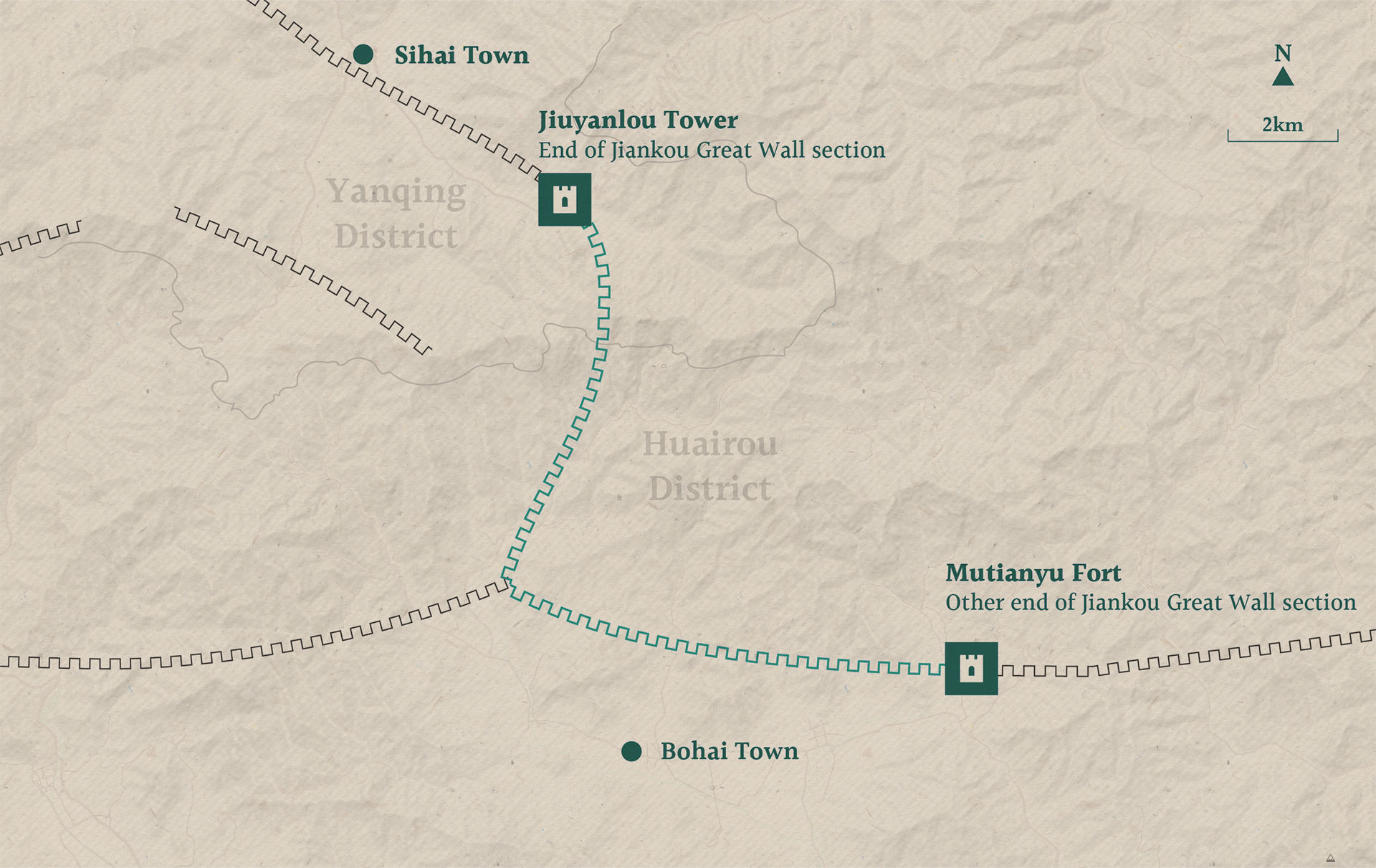

Two workers at the repair site for the Jiankou Great Wall section in Beijing, May 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

Systematic, nationwide efforts to protect the Great Wall began only in the mid-2000s. By that stage, the scale of the damage done over previous decades had become clear.

In 2005, a survey of the Great Wall around Beijing found that only one-tenth of the monument remained in good condition, according to Dong Yaohui, chief secretary of the China Great Wall Society, a government-affiliated conservation group.

Before, conservation had been a local issue, handled by a patchwork of lower-level authorities spread across 15 different Chinese provinces. These local projects tended to be poorly funded, though there were exceptions.

During the 1990s, the city of Linhai in eastern Zhejiang province maintained its 1,500-year-old city walls — known as the Southern Great Wall — by raising millions of yuan through voluntary donations. “The slogan was, ‘each person donates a brick, we’ll restore the ancient city wall,’” says Peng Liansheng, director of the city’s cultural relics bureau.

The turning point came in 2006, when the Chinese government added most of the Great Wall to its list of national-level protected cultural sites and made central government funds available for renovation projects.

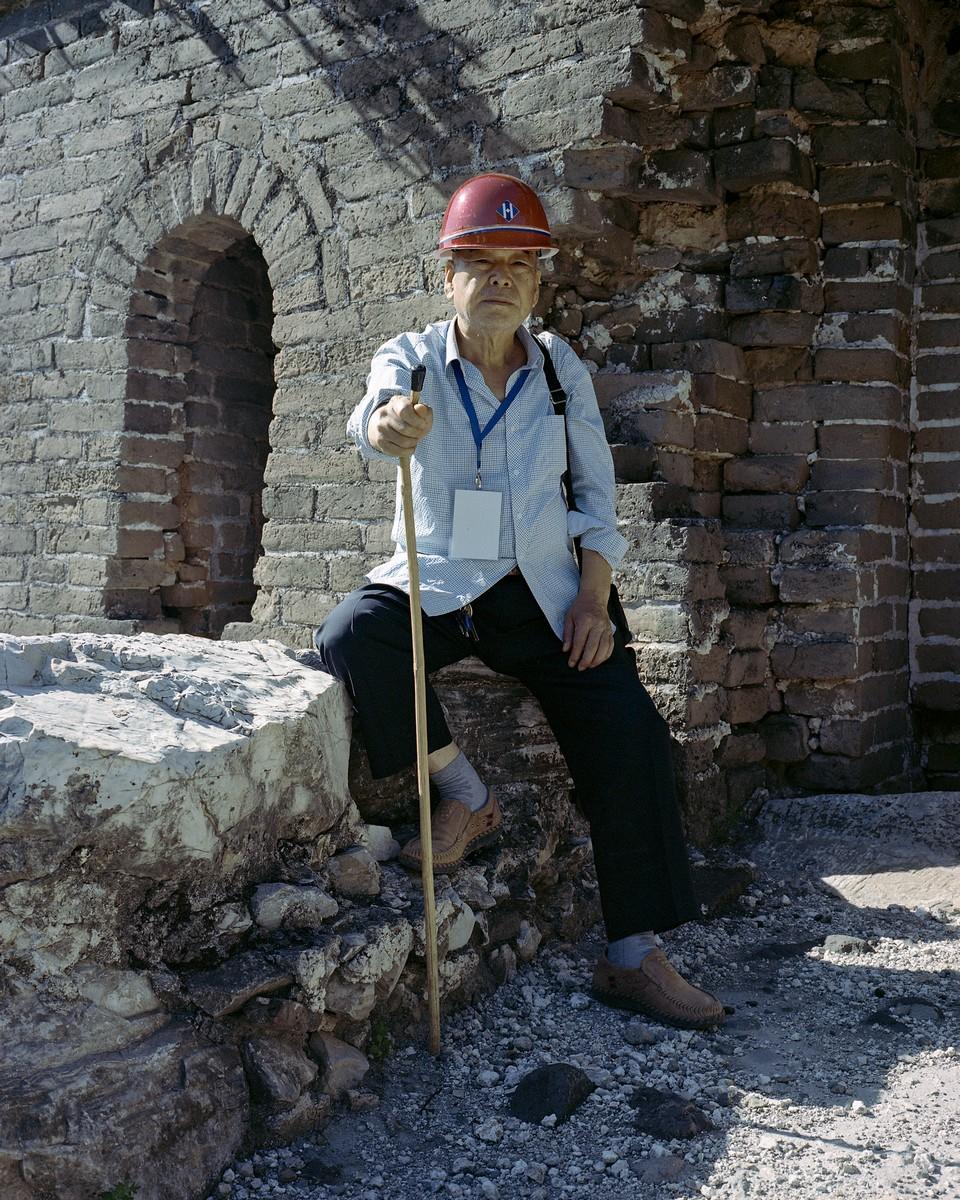

Zhang Tong, head of Huairou’s cultural relics bureau, poses for a photo at her office in Beijing, May 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

From then on, preserving the wall became a priority for officials across China. When Beijing’s northern Huairou District first surveyed the Great Wall during the 1980s, it was done on a shoestring budget. “We used tape measures for length and box rules for height,” says Zhang Tong, a member of the survey team, who is now head of Huairou’s cultural relics bureau. Between 2007 and 2016, by contrast, the Beijing government invested 374 million yuan in Great Wall repairs.

Cheng, the architectural engineer, started work in Jiankou in 2016, the same year China created its first comprehensive Great Wall protection plan as part of the country’s 13th Five-Year Plan, which runs to 2020.

From the beginning, the pressure on Cheng has been intense. The Great Wall has reasserted itself as a central symbol of national pride in recent years, and repair projects are subjected to close scrutiny by the public and the country’s leaders alike.

“When people talk about China, they think of the Great Wall,” said President Xi Jinping during a visit to Jiayuguan, the western end of the Ming dynasty wall, this past August. “We must attach great importance to the protection and inheritance of history and culture, and protect the enduring roots of the Chinese national spirit.”

LeftTop: The mountain road to the Jiankou Great Wall section; RightBottom: Worker Fu Zuorui, 58, from Chengde in Hebei province, poses for a photo at the Dazhenyu Great Wall section in Huairou District, Beijing, May 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

LeftTop: Water pipes for repair work at the Dazhenyu Great Wall section; RightBottom: Two workers stand on rocks at the foot of the Dazhenyu Great Wall section, Beijing, May 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

LeftTop: A repair site for the Jiankou Great Wall section; RightBottom: Worker Zhang Junfeng, 59, from Chengde in Hebei province, poses for a photo at the Dazhenyu Great Wall section, Beijing, May 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

Previous restoration projects have generated controversy. Just as work began in Jiankou, photographs emerged of a recently repaired section of Xiaohekou, a part of the Great Wall in the northeastern Liaoning province. The historic stonework appeared to have been covered with a thick layer of cement, attracting widespread criticism.

According to Cheng Yongmao, officials in Xiaohekou had followed standard practices during the project. But the public reaction, he says, suggests that simply repairing the wall isn’t enough: The works also need to reflect people’s expectations of what the Great Wall should look like.

“After the work, the wall should look as close to its original state as possible,” says Cheng. “A nonprofessional should not be able to tell the difference.”

Architectural engineer Cheng Yongmao poses for a photo in Beijing, May 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

Cheng’s team goes to great lengths to uphold the principle of minimal intervention. More than 95% of the bricks used are original, and additional materials are kept to an absolute minimum, he says. Trees growing out of the wall are removed only if they are likely to cause structural damage.

Even so, it took two years for the government to finally approve Cheng’s restoration plan for Jiankou, after five rounds of revisions, according to Zhang. Work began at “Eagle Flies Facing Upward” and the “Heaven’s Ladder” — two tourist hot spots where accidents often occur.

The extreme logistical challenges associated with repairing mountaintop walls cut off from modern roads have made the work slow going. While donkeys transported the building materials up the steep hillsides, workers had to carry the 40 kilogram steel bars used to lift the bricks onto the ramparts.

“After the work, the wall should look as close to its original state as possible.

Cheng Yongmao, engineer

After two days, many of the workers who had grown up on the plains surrounding Beijing had quit, their knees swollen from the hours of climbing, according to Cheng. The remaining laborers eventually completed repairs at the two sites in 2017.

Work began on the third phase of the repair project — which focuses on the eastern edges of Jiankou — in late April.

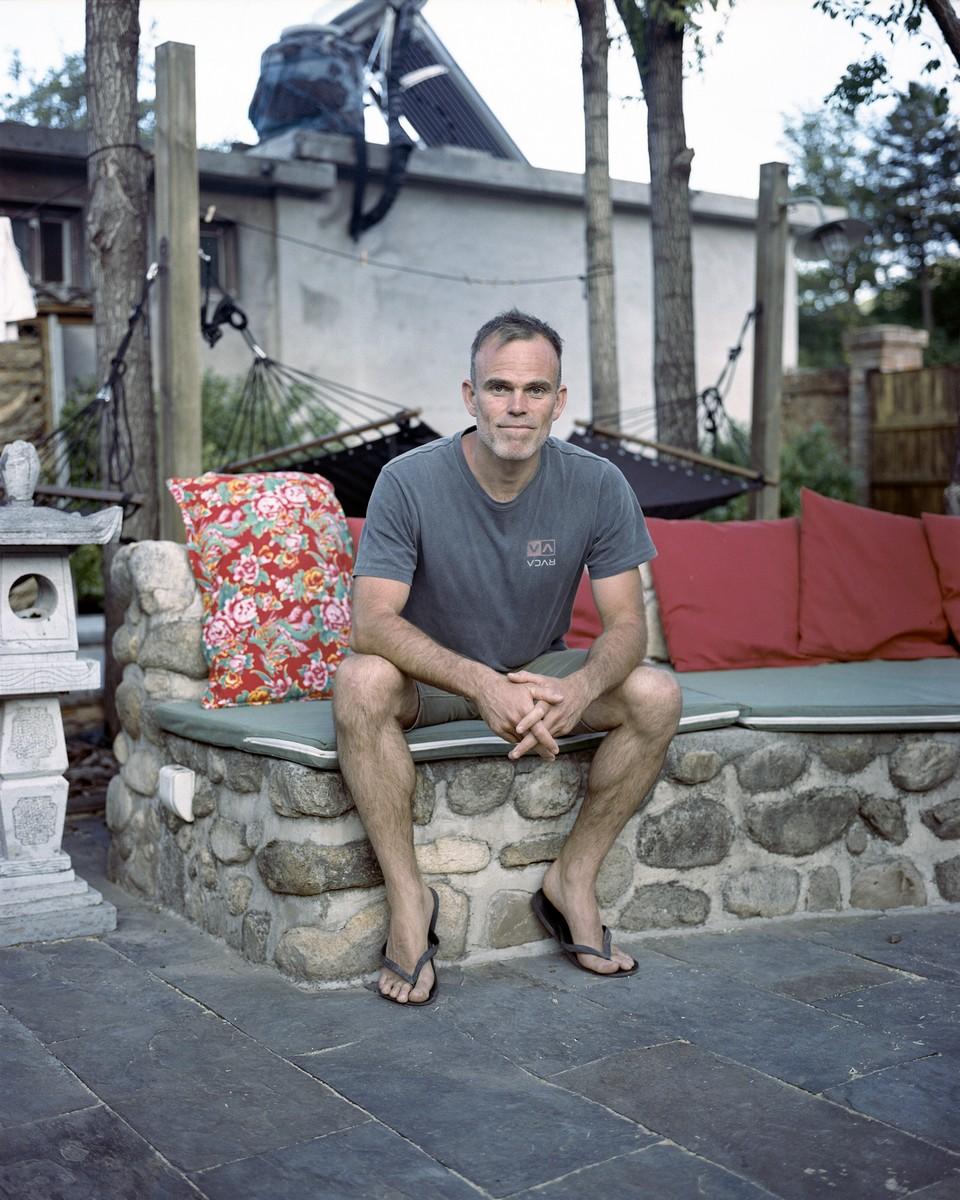

In Xizhazi, residents have mixed feelings about the restorations. “It feels very much like the original — and also safer,” says Jade Gray, a New Zealander who has rented a house in the village since 2003. Lin Jiang, however, tells Sixth Tone that “Eagle Flies Facing Upward” feels “too new” and “lacks the scent of antiquity.”

Jade Gray, 45, a New Zealander living in Xizhazi, poses for a photo in Beijing, May 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

Locals also express unease about how future conservation efforts might affect the economy. This past November, the Chinese government announced ambitious new plans to create three enormous new “national cultural parks” along the Great Wall, the Grand Canal, and the route of the Red Army’s Long March in the 1930s.

Beijing, which is home to 520 kilometers of the Great Wall, is at the forefront of the new protection drive. In early 2019, the city designated an area of 5,000 square kilometers — around one-third of the capital’s land mass — as a Great Wall Cultural Belt, where economic development will be restricted.

The new plans will have a direct impact on Xizhazi. The village has been classified as a “development control area,” meaning new construction projects are forbidden. Any illegal development can be punished with fines of up to 500,000 yuan.

Cheng Yongmao at the Dazhenyu Great Wall section in Beijing, May 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

For many locals, especially those who planned to cash in on the tourism boom by opening homestay-style hostels, the conservation efforts are a source of frustration. In recent years, the government also prevented the village from charging entry fees to hikers.

“The village only has obligations to protect (the Great Wall), but no power to plan and develop,” says Lin. “We are guarding a golden rice bowl but begging for food.”

Zhang, the Huairou District official, agrees that the regulations provide little benefit to residents in Xizhazi. “You can’t build high-rises,” says Zhang. “The challenge is how to rationally develop the area and plan the local homestay business.”

Wang, a restaurant and homestay owner in Xizhazi who declined to reveal his full name for privacy reasons, says he is pessimistic about the future of the village. In recent years, the government has restricted the number of people climbing Jiankou and broadcast warnings about the safety risks of doing so, which has impacted visitor numbers. He also fears that the government will relocate villagers away from the Great Wall, as part of the cultural belt policy.

“We are guarding a golden rice bowl but begging for food.”

Lin Jiang, villager

“All I wish is to live my life and make enough money to provide food for my family,” says Wang. “I hope the government can renovate the village to make it beautiful, so more visitors will come.”

The conservation policies have, however, brought Wang some additional income. In early 2019, the villager was among 131 people recruited by Huairou District officials to become Great Wall keepers. He is paid 2,000 yuan per month to spend two mornings a week hiking Jiankou, searching for potential safety risks, picking up trash, and warning travelers not to climb dangerous sections of the wall.

The new job suits Wang well. Even if he is not on duty, the keeper says he likes to spend his days in the mountains. He serves Sixth Tone a dish made with muli bud, a plant that grows on the cliffs of Jiankou, which he hand-picked himself.

“I’m probably one of the best in the village at climbing,” says Wang. “It’s nice to look at what the ancient people left us.”

A view of the Jiankou Great Wall section in Beijing, May 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone