The Western Wall:

Protecting China’s Ancient Frontier

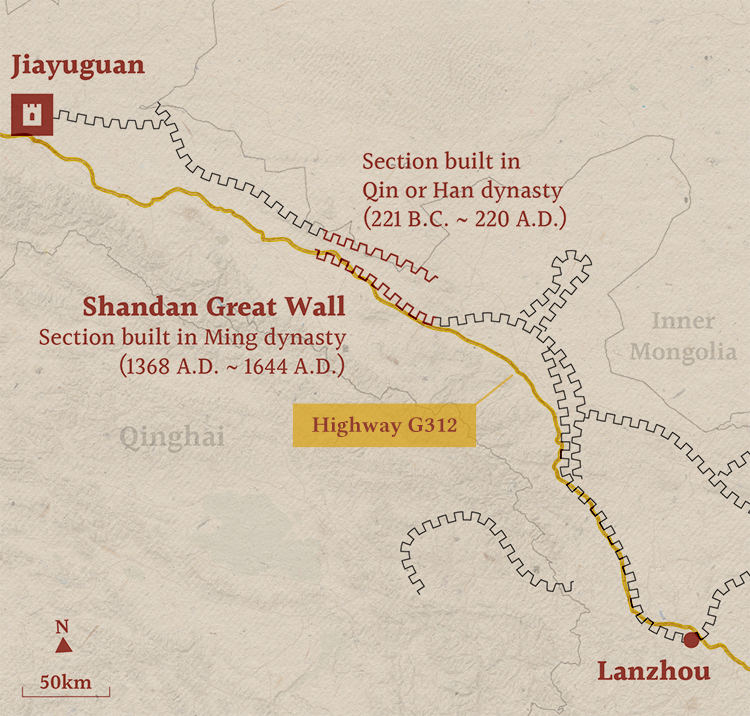

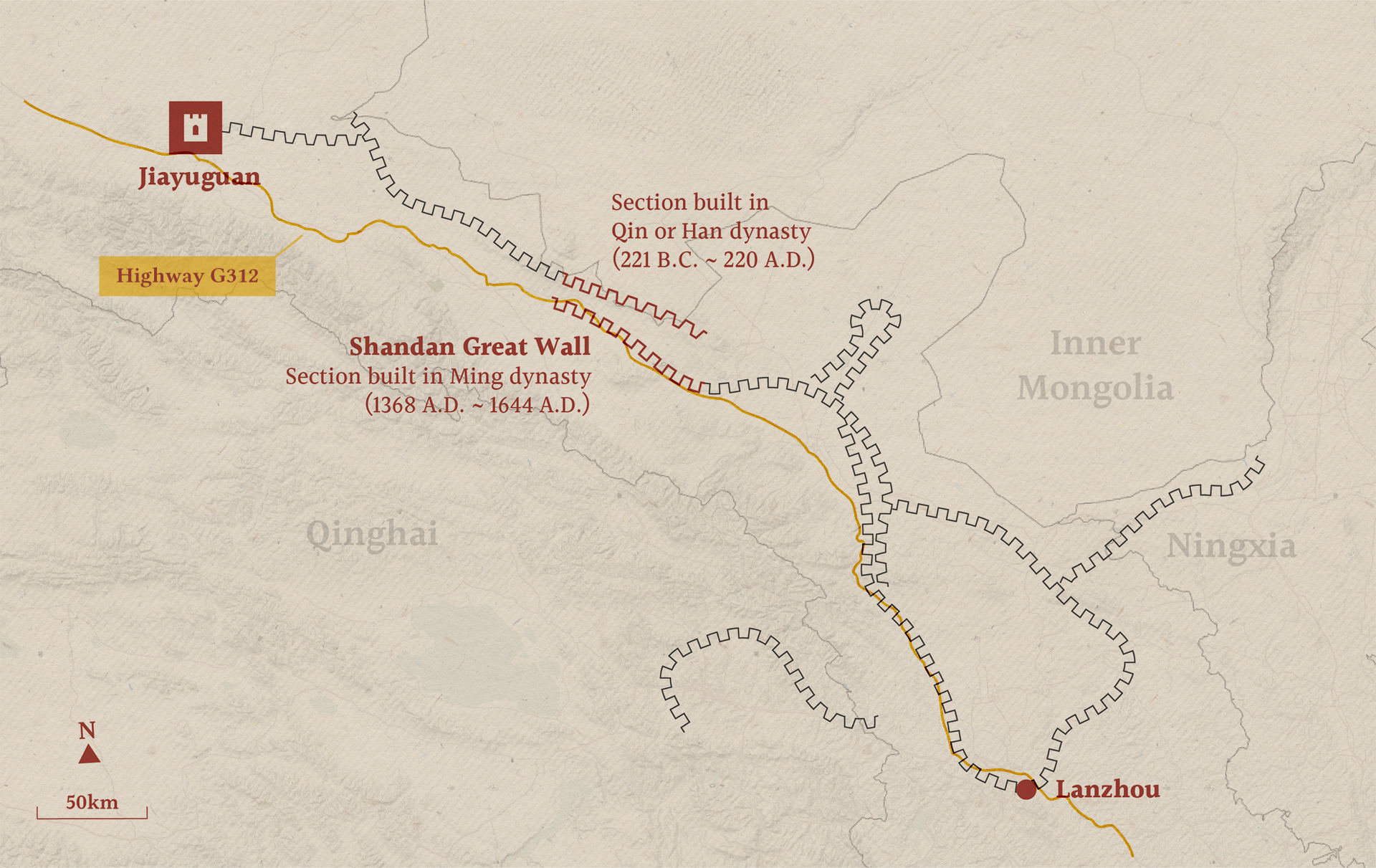

GANSU, Northwest China — At Shandan County, an arid region on the edge of the Gobi Desert, China’s “Mother Road” hits the Great Wall.

Highway G312 runs the entire breadth of China — from eastern Shanghai to the country’s western border with Kazakhstan — and it has no time to slow down in Shandan. The road cuts straight through the 2-meter-high fortifications, before veering left and continuing its long westward climb.

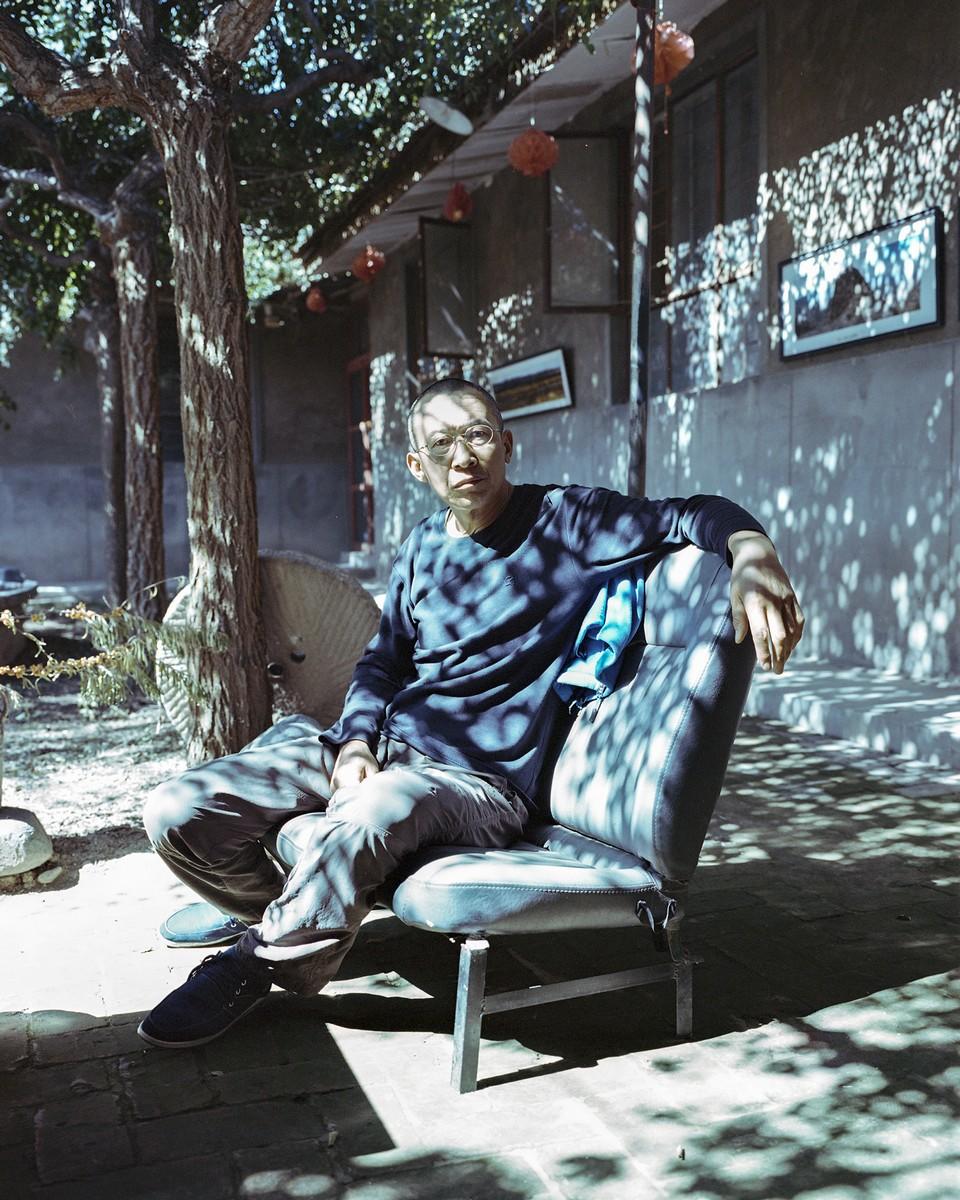

Chen Huai’s jeep is parked just behind the gaping hole in the ancient ramparts, in a dusty rest area named the Great Wall Post. Across the road, there’s a small Great Wall exhibition hall and a ramshackle courtyard where Chen has lived for nearly 20 years.

A slightly hunched figure in his late 60s, Chen is something of a legend in this remote part of Gansu province. He’s an amateur historian and photographer who’s become an expert on the Shandan section of the Great Wall, as well as a leading advocate for its conservation.

Shandan sits close to the Great Wall’s western extremity — over 1,500 kilometers from the iconic gray ramparts of Badaling near Beijing. Military outposts were first established here over 2,000 years ago during the Qin dynasty, to protect the newly united Chinese empire from attacks by Mongolian tribes. The fortifications were further strengthened under the Han, and then again during the Ming dynasty.

Unlike the more famous, Ming-era wall near the current Chinese capital, the ramparts in Shandan are mostly constructed from sand-colored mud. They almost appear as natural rock formations, rising up from the dry plains like a coastal shelf. They’re also remarkably well-preserved. Experts have labeled the county a “Great Wall open-air museum,” as it’s home to over 150 protected sites.

But economic development threatens to tarnish this unique historical legacy. As Shandan promotes itself as a Great Wall tourism destination — with more than 3.6 million tourists visiting the county each year — many worry that prosperity will come at the expense of the monuments driving the region’s growth.

Chen shares this concern. He tells Sixth Tone his ties to Shandan go back to the ’70s, when he was sent to work the county’s fields for three years during the Cultural Revolution. He returned to the area and bought the patch of land next to the G312 in 1998. Ever since, his life has been intertwined with the Great Wall.

A view of the Shandan Great Wall section in Shandan County, Gansu province, September 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

Chen spent years as an itinerant writer and photographer, documenting Shandan’s connection with the wall and writing two self-published books on the subject. He makes a living by hosting tourists visiting the monument in his courtyard home, as well as selling his books from a stall in the rest area.

Since 2007, he has also served as one of Shandan’s 84 Great Wall keepers, patrolling the wall and reporting any damage or safety issues to the local cultural relics bureau. Chen is paid 3,000 yuan ($430) per year for his efforts.

At times, however, Chen says the local government fails to deal with the issues he reports. Farming and grazing livestock are banned near the Great Wall, but villagers are still growing crops in at least one area, he says. When he pointed this out to the cultural relics bureau, the officials told him it was the county government’s job to manage farmers — and nothing was done.

Chen Huai poses for a photo in his yard in Shandan County, Gansu province, September 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

Local officials tell Sixth Tone that protecting Shandan’s Great Wall heritage is extremely challenging given their lack of resources.

“There are hundreds of cultural relics and the (Shandan) Great Wall is hundreds of kilometers long, but we have only three staff members,” says an official surnamed Han at the Shandan cultural relics bureau. “We have so much to do, it’s impossible to manage it all perfectly.”

For villagers in Xiakou Pu, a small settlement near the Shandan wall, meanwhile, the government’s ability to protect the region’s heritage isn’t a major concern. They’re more interested in how officials can help them attract tourists.

“We’re a poor village, and we have to rely on the tourist industry to develop,” says Li Shuxiang, a 63-year-old Xiakou resident. “The government is planning, but I don’t know when the tourism development will start here.”

Li Shuxiang poses for a photo in Xiakou Pu, Shandan County, Gansu province, September 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

Inside the Shandan government, officials have high hopes for the recently completed Great Wall Post. They’ve been focusing on the construction of the rest area for the past two years, hoping to lure visitors traveling between the provincial capital Lanzhou and the famed Great Wall fort Jiayuguan. “It’s kind of a calling card for our area,” says Han.

But things feel like they’re moving slowly in Xiakou, according to Li. The village recently elected a new leader named Fang Wei, largely due to the young entrepreneur’s ambitious plans to expand tourism in the area. At the moment, though, tourists are reluctant to stay long, as Xiakou lacks the modern amenities most travelers expect.

“The (Shandan) Great Wall is hundreds of kilometers long, but we have only three staff members.”

Han, local official

Fang’s wife, Zeng Li, tells Sixth Tone that local businesses can only offer a few activities, such as camel rides and meals inside traditional Mongolian yurts. Overnight accommodation is currently lacking. Zeng and her husband are also trying to help local farmers make money by selling their lamb and crops via e-commerce platforms.

“The prospects are good, but we have few human resources,” says Zeng. “In the village, young people are very rare. There are a lot of elderly people.”

LeftTop: Liang Zhong, 36, head of the repair workers, poses for a photo near the Shandan Great Wall section; RightBottom: A part of the Great Wall in need of repair in Shandan County, Gansu province, September 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

LeftTop: Duo Chenghua, 47, poses for a photo in front of the Shandan Great Wall section; RightBottom: Workers repair the Great Wall near Xiaozhai Village, Shandan County, Gansu province, September 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

LeftTop: A tourist poses for a photo at near Danxia landforms; RightBottom: A view of Danxia landforms in Zhangye, Gansu province, September 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

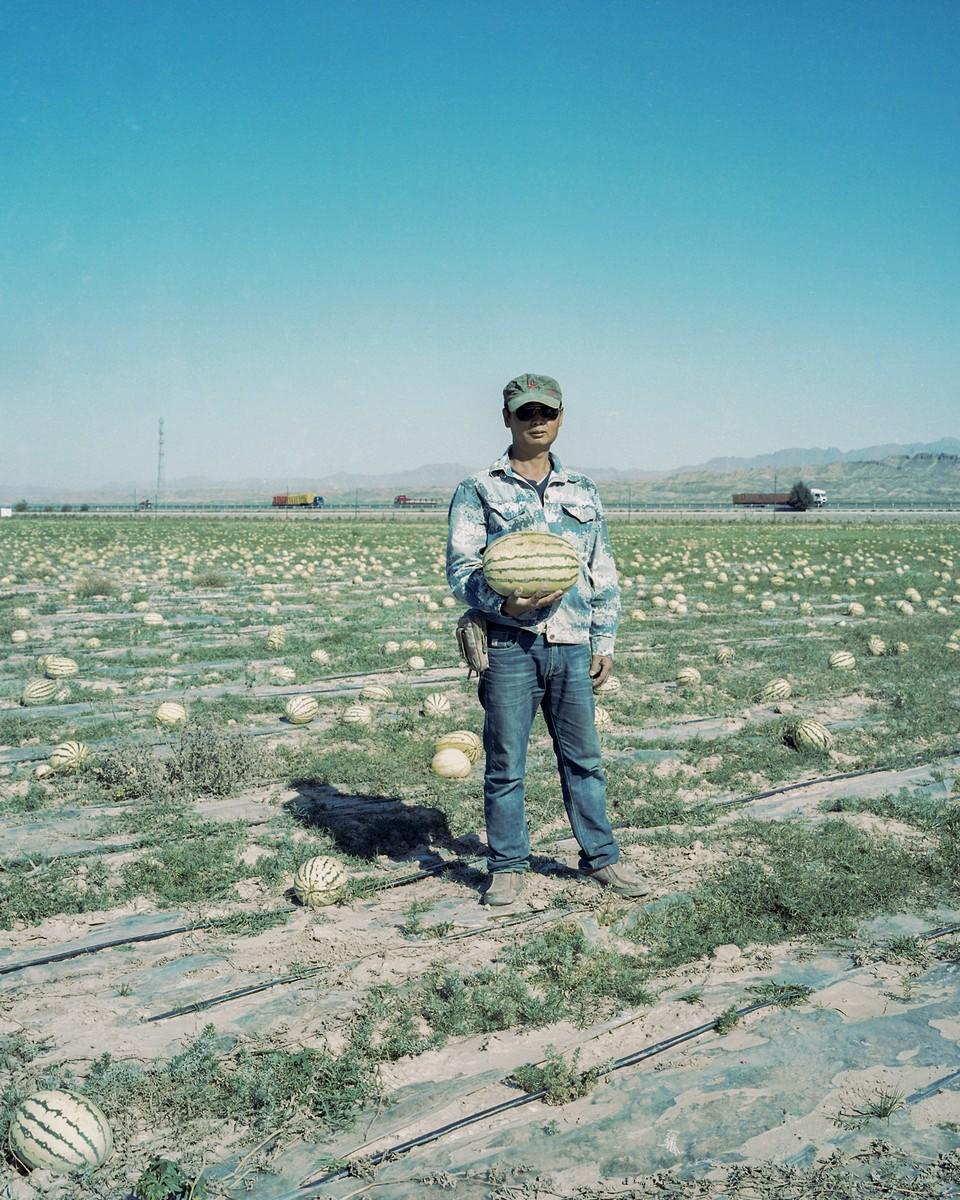

Wu Junjie is one of the few members of the younger generations choosing to stay in Shandan. He has set up a watermelon farm just outside Xiakou and sells the fruit online under the brand name Great Wall King.

The business got off to a rocky start. In 2019, the local government launched a slew of infrastructure projects designed to make it easier to do business in the county, reconstructing roads, rebuilding public toilets, and reinforcing flood defenses. The work, however, left the roads blocked for months, making it impossible for Wu to ship his melons to his clients.

Wu Junjie poses with a watermelon in Shandan County, Gansu province, September 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone

Of the 1,800 mu (120 hectare) watermelon harvest, Wu estimates he was unable to sell 1,600 mu of it. He’s hopeful things will work out better this year. “Now, it (the road) is much wider, and three cars can pass easily,” says Wu.

The development even threatens to uproot Chen Huai. The local government is considering demolishing his courtyard to expand the facilities around the Great Wall Post, he says, but the plans have yet to be confirmed.

Chen appears philosophical about the prospect of being relocated. He tells Sixth Tone he has only one wish for the future.

“When I get old and die, I hope there’ll be a memorial pavilion or tombstone in this place to commemorate someone who lived here for so many years,” says Chen. “For the inscription, I hope they write, ‘the Great Wall recluse.’”

A camel standing in the grass near the Shandan Great Wall section in Shandan County, Gansu province, September 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone