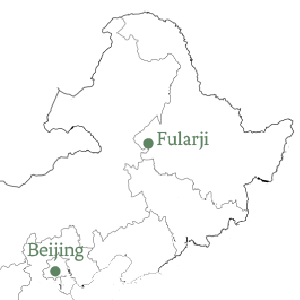

Fularji, Heilongjiang province

Located in Fularji, a district of Qiqihar in the northeastern Chinese province of Heilongjiang, the headquarters of China First Heavy Industries (CFHI) boasts an interesting nugget of trivia: It is situated farther north than any other state-owned enterprise. The company’s origins can be traced back 60 years to the amalgamation of a heavy industry factory, a thermal power station, and a steel mill. On a good day, CFHI churns out high-grade energy and industrial equipment that’s sold across the country.

The factory’s peak lasted until the late 1990s, when the booming metropolises of China’s coastal regions pushed able-bodied workers out of the interior and onto trains heading south. In an attempt to stem the loss of staff, CFHI moved its logistics, technological development, and marketing teams to coastal cities like Shanghai, Dalian, and Tianjin.

At roughly the same time, higher education institutions began to leave Fularji, and the city’s state-owned chemical, glass, and textile factories either went bankrupt or were restructured by the government. Regional industry shrank, and local authorities took over the cradle-to-grave provision of social services once provided by state-owned enterprises.

Touch the icons below to view the milestones in each company's history.

Qiqihar New Eighth Brick Factory

1976 Established as Qiqihar Eighth Brick Factory

1994 Merged with Qiqihar Ninth Brick Factory

1997 Stopped production

2005 Remodeled into a joint-stock company, but yet to resume production

Beifang Glass Company

1986 Established as Heilongjiang Glass Factory

1998 Restructured after applying to file for bankruptcy

2002 Merged with and restructured by Beijiang Group

Heilongjiang Heihua

1970 Established as Heilongjiang Chemicals Factory

1997 Formed a new company with other factories and enterprises

2005 Put under the administration of another company after asset restructuring

2008 Put under the administration of a ChemChina subsidiary

Beiman Special Steel

1954 Established as Beiman Steel Factory

1970 Demoted from national-level to local-level factory

1992 Incorporated with other businesses into a larger conglomerate

2003 Restructured and merged with a Liaoning-based company

2017 Filed for bankruptcy and restructured again

China First Heavy Industries

1960 Established as First Heavy Machinery Factory, the largest of its kind in China

1993 Incorporated into a conglomerate under its current name

1998 Created 13 independent units from subsidiaries

2005 Started construction on an R&D center in Tianjin

2017 Turned a profit for the first time in two years

Fularji General Power Plant

1955 Established as Fularji Thermal Power Plant

1981 Merged with Fularji Second Power Plant, which went into operation a year later

1997 Restructured into a limited liability company

2002 Put under the administration of a state-owned power company

Heilongjiang Zhongtian Textile

1968 Established as Fularji Hongbaoshi Textile Factory

1988 Approved to become a large corporate enterprise

1994 Divided into three factories, two of which later went bankrupt

2001 Became a private company

2005 Divided into a state-owned company and a private company

Qiqihar Cement Factory

1954 Established as Qiqihar Cement Products Factory

1996 Declared bankruptcy

1997 Divided into two separate enterprises

2002 Merged to become part of Beijiang Group

Heilongjiang Qiqihar Sanjiang Cement Products Company

1954 Established as Qiqihar Cement Products Factory

1996 Declared bankruptcy

1997 Divided into two companies

2001 Approved as a joint-stock company after a period of difficulty

An aerial view of Heilongjiang Heihua chemical factory.

Fularji’s development has essentially been on hold for the last 20 years.

“Fularji” is a Chinese translation of the Daur word hulane’rige, meaning “red riverbank.” The district’s name is derived from its location along the banks of the Nen River, as well as from the area’s abundant red agate deposits. In the early 20th century, bolstered by its position along the Chinese Eastern Railway, Fularji grew into a commercial hub.

Six decades ago, a wave of engineers, retired soldiers, and their families were sent north to the harsh, cold climate of northeastern China. There, they worked under military-style Soviet leadership to set in motion the gears of a new, industrial China.

Suffering and honor often go hand in hand, and the area’s proud workers — whose efforts once earned them a stop on top Chinese leaders’ inspection tours — aged quickly. “Our parents’ generation gave their youth to this place and left us here,” said Ying, a 50-year-old second-generation resident.

Those now nearing retirement age still sometimes stroll through the district’s Hong’an Park. Located on the west bank of the Nen, the park was inspected by Premier Zhou Enlai himself when it opened in 1956. Walk toward the riverside and you’ll find a giant red orb ringed by five stainless steel statues: a worker, a peasant, a businessman, a student, and a soldier. Their shining surfaces are a testament to the region’s former industrial might.

Abandoned structures stand amid barren trees and snow in Fularji’s parks.

When I visited in January, however, a flyer posted beneath the worker’s metal feet called for help finding a lost cow. Villagers who reside on the outskirts of the city make a living by grazing cattle in the public park, with few people bothering to watch over them. Behind the statue, rusted industrial machinery sits quietly amid the snow.

Traces of the 1950s are scattered across Hong’an Park. Walk past the out-of-service amusements and you’ll come across a pillbox-style public restroom. Two-thirds of the building is set aside for men, with only the remaining third open to women — a design choice that reflected the mainly male demographic of Fularji’s mid-century immigrants. Two years would pass before their wives and families could join them.

Head toward CFHI’s main gate and you’ll encounter the largest statue of Chairman Mao anywhere in China. Cast completely from stainless steel cut by this very factory, it weighs more than 33 tons and stands over 10 meters tall. Visible regardless of which direction visitors are coming from, it is a towering monument to a bygone era, and one of the best-maintained landmarks in Fularji.

A disused Heilongjiang chemical plant has started to become overgrown.

CFHI manufactures military and nuclear equipment, steel, automotive parts, and nonferrous metal products. At the start of the year, the factory began a large round of “competitive hiring.” Factory heads emphasized the need to increase efficiency and promote talented workers, but the fact remains that after the recruitment drive, total staff numbers had been cut from more than 11,000 to just over 8,500.

Since then, employees have walked through the factory gate briskly, not daring to slow their pace. Factory management penalizes those who arrive at their posts late, and employees stand fastened in place like screws.

Finding a job isn’t a problem, but parents don’t want their kids to become factory workers. - Chen Yu, teacher at CFHI Technician College

Most young people prefer to work in the slightly freer atmosphere provided by the service industry. CFHI Technician College, an institution with a rich industrial tradition, has recently begun offering service-oriented majors, including courses in e-commerce and cosmetic science. The school long ago severed its formal ties with CFHI, and while students are still able to intern at the company, only a select few will ever be hired on. As an instructor named Chen Yu put it: “Finding a job isn’t a problem, but parents don’t want their kids to become factory workers.”

The smell of coal hangs heavy over Fularji; the air is cold and dusty. Walking from factory to factory through the dense smog feels like passing through a succession of self-contained communities.

Wanping District is a new “village” built to house workers at the Beiman Special Steel plant. Its community message boards are now covered with signs advertising homes for sale. A young girl plays on a swing set that creaks as she rocks back and forth.

Nearby homes sit empty and have long since fallen into disrepair. At Beiman’s old culture center, Sansan Cultural Palace, the characters for “welcome” have long since faded from the broken windows. On the other side of the center sit villas that formerly housed Soviet industrial experts. Elegant yet decrepit, they are the opulent legacy of yesteryear.

-

An old karaoke parlor in downtown Fularji now sits empty.

-

A local man performs a traditional sword dance.

-

A rusted roller coaster rail stands abandoned in Hong’an Park.

Every road in the residential district in front of the CFHI factory leads to the factory gate. A retired second-generation factory employee points out the place where the dorms for unmarried employees used to sit: “When my father first came to Fularji, that’s where he lived. It was such a lively place.”

But many residents have already moved away. Behind the darkened hallway windows of the monolithic socialist architecture, private businesses have sprung up: a ramshackle hostel, a convenience store, a restaurant, a children’s training school.

CFHI is a growing company, but it’s not growing in Fularji. All that remains here is a manufacturing base and the company’s nominal headquarters. The homes designated for employees of the company’s design institute sit largely empty and are priced in the low six figures. The older brick buildings are even cheaper and emptier, costing about 80,000 to 100,000 yuan ($12,000 to $15,000) per unit. Even new homes, which only cost about 3,600 to 3,700 yuan per square meter, struggle to find buyers.

The majority of the 240,000 or so people still living in Fularji are middle-aged workers nearing retirement. This so-called rearguard tends to congregate in the event space of Dajiating Mall, where they play cards and pingpong. Many have only stayed to take care of their aging parents: Now in their 80s and 90s, members of the first generation of workers are unable to return to the hometowns they left all those years ago.

Lin Zi

“My parents abandoned me, and I make money by doing drag performances on a livestreaming app.”

Li Zhi

“I don’t have a house, and I spend most of my time at the internet café. When I’m tired, I go to a cheap hotel to rest.”

While the area is still home to some people of working age, anyone who has managed to save money intends to move away in the future. Most say they want to retire to a city with a warmer climate and better air. “A friend of mine moved to Sanya [in southern China’s Hainan province], and pretty soon her tracheitis and arthritis began to improve,” Chen said eagerly.

-

Lin Zi

“My parents abandoned me, and I make money by doing drag performances on a livestreaming app.”

-

Li Zhi

“I don’t have a house, and I spend most of my time at the internet café. When I’m tired, I go to a cheap hotel to rest.”

-

Twins surnamed Huan

“We sell clothes, but we didn’t make any money this year. We plan to move to Zhejiang province.”

-

Hui Zi

“I work at the bar at night, and I have another job during the day so I can earn a living.”

Most of the rearguard are in their 50s and 60s, and have plenty of siblings. To many of them, this is a boon: As long as someone stays behind to take care of the elders, the others are free to range as far as they like.

Twins surnamed Huan

“We sell clothes, but we didn’t make any money this year. We plan to move to Zhejiang province.”

Hui Zi

“I work at the bar at night, and I have another job during the day so I can earn a living.”

The majority of leavers maintain jobs in heavy industry. “CFHI operated on a large scale, so I’ve used every kind of machine and can handle them all,” boasts Zhang Ying, a retired CFHI worker whose relatives now work in the company’s Shanghai branch. “Compared to workers from northeastern China’s other cities, technicians from Fularji are capable of thriving anywhere.”

The ties binding Fularji’s third generation to the area are even more tenuous. While Fularji has no shortage of talented young people willing to become high-level blue-collar workers, the city is considered “too cold” — winter temperatures plunge as low as minus 40 degrees Celsius — and such individuals prefer to look for jobs farther afield. In recent years, the government has tried to recruit local technicians, and as a result of reforms to vocational education, students can now enroll in a program at CFHI Technician College and earn a vocational diploma. Yet better career prospects mean more opportunities to leave: “I guess about 80 percent of the college’s graduates now work elsewhere,” said Li Yaying, the head of the technical school.

An ’80s-style restaurant next to Hong’an Park.Like other cold and struggling cities in northeastern China, Fularji has a vibrant livestreaming culture. Broadcasters usually record themselves at home with their computer cameras. Most of the parents struggle to understand why their youngsters don’t try to find positions at CFHI after they graduate from college, but the children see no guarantee that the factory will provide them with a better life.

An ’80s-style restaurant next to Hong’an Park.Like other cold and struggling cities in northeastern China, Fularji has a vibrant livestreaming culture. Broadcasters usually record themselves at home with their computer cameras. Most of the parents struggle to understand why their youngsters don’t try to find positions at CFHI after they graduate from college, but the children see no guarantee that the factory will provide them with a better life.

In an area where a salary between 5,000 and 6,000 yuan a month is considered high, even comparatively well-off young people rely on their parents’ savings to find their footing in a major city like Beijing, Shanghai, or Guangzhou, though the vast majority still struggle to buy homes there. Some choose a less risky means of escape, settling in the regional hub of Qiqihar, Heilongjiang’s second-largest city, which not only boasts a lower cost of living than first-tier cities but also allows young adults to return home and visit their families from time to time. Once their grandparents have passed away, this generation will bring their parents to the city to live with them, while also setting their own children up with the opportunity to move to even larger cities in the future. By that time, Fularji will perhaps more closely resemble a ghost town.

Some ex-factory workers continue to work in Fularji, opening stalls at Dajiating Mall or starting street-side restaurants. In years past, migrants from Zhejiang province in eastern China often came to Fularji to hawk furniture and leather shoes — back when workers still had money to spend. These days, those same workers find themselves waiting on others.

Flashing neon lights adorn the facades of nightclubs in Fularji.

Flashing neon lights adorn the facades of nightclubs.

Faced with a declining population and a deteriorating economy, Fularji’s leadership has tried to attract new industrial projects. Yet such ill-timed endeavors have only increased people’s desire to leave. In August 2016, Fularji signed a deal with Zijin Mining for a smelting project that would occupy 500,000 square meters of land and bring an investment of about 4 billion yuan.

Zijin has been linked to several pollution cases, however, and many residents doubted its ability to keep the problem under control. Worried that the company would secretly dump copper-laced pollutants — a chronic problem in the region and one that led to the closure of a Heilongjiang chemical plant and other industries — many locals turned against the plan. Although their concerns failed to attract the interest of major media outlets, many simply chose to vote with their feet, and moved out.

In Fularji, even the local entertainment feels like an elegy for the past. In 2017, as the bells rang in the new year, local retirees took the stage at Dajiating Mall in turns, singing and dancing to the accompaniment of sound effects meant to invoke the factory floor. Wholly uninterested in the crowd’s reaction to their performances, they evinced a happiness that was pure and direct in a way so rarely seen these days. Meanwhile, younger residents stayed home, performing skits in front of webcams for China’s internet users.