Longjing, Jilin province

The Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture is crammed into the gap left by the hulking shapes of its nearest neighbors: Heilongjiang province to the north, North Korea to the south, and the Russian province of Primorsky Krai to the east.

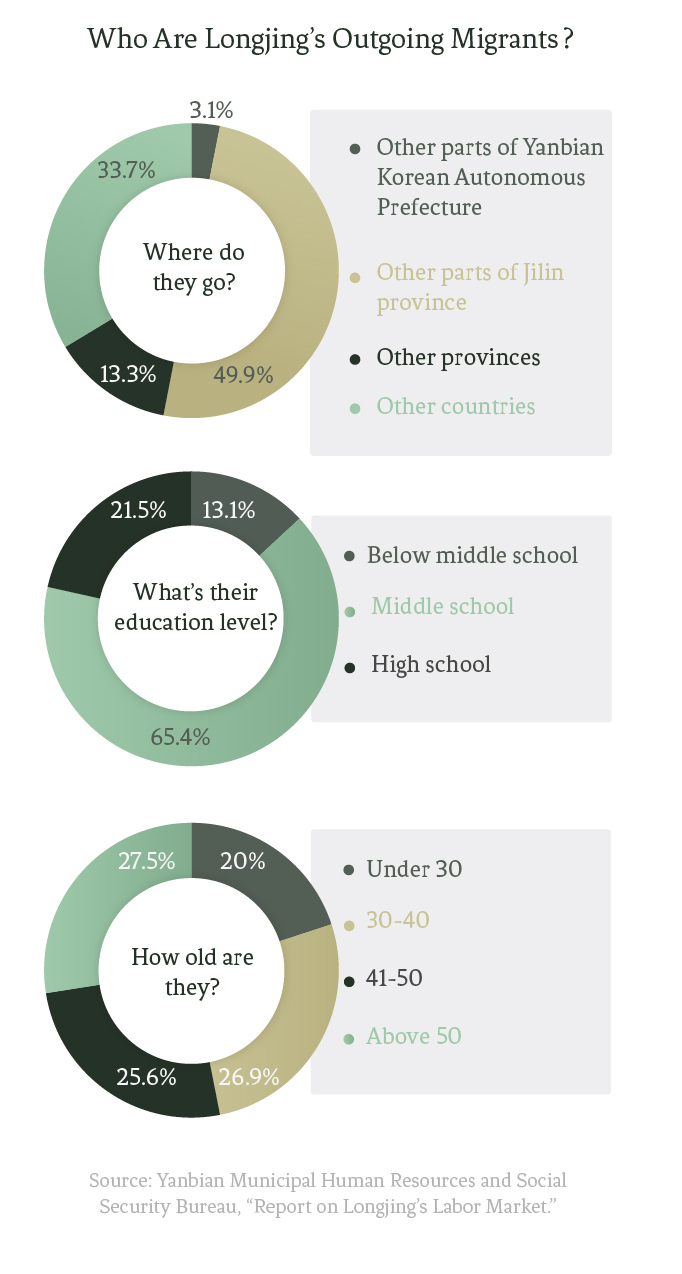

Last winter I visited Longjing, one of Yanbian’s biggest cities. Sixty percent of Longjing’s residents are ethnic Koreans, but many have left town in search of better opportunities elsewhere. The mornings were silent. In a roadside internet bar, groups of children were playing computer games, the sound of clicking mice cutting through the quiet. Outside, a couple of sanitation workers idly swept the shopping streets.

There is no rush hour in Longjing. During work hours, most of the cars you see are heading toward government buildings.

From 1907 to 1937, the Japanese occupied Longjing and made it the administrative center of the region. Later, the municipal government sat on the site of the former Japanese consulate. The city hall recently moved to a brand-new four-story building nearby, and the old consulate building was converted into a museum commemorating the Japanese occupation. Occasionally, schools organize field trips to the museum, and the exhibition halls fill with gaggles of chattering children. But usually, it sits empty and untended.

In Longjing, you either work for the government, or you run a business out of your house. - Li, an online shop owner

Until the 1990s, Longjing was a thriving base for heavy industry. Lots of mines and factories were located nearby, and more people lived here than in the prefectural seat, Yanbian. “Before, it didn’t matter that Longjing wasn’t large,” said a longtime restaurant owner, explaining why he went into business here. “Longjing was the center of the whole prefecture.”

But now it is difficult to earn a living in Longjing. At the entrance to each apartment block, posters are hung all over the walls, advertising eggs and milk, cleaning services, and the homes within.

-

The groundbreaking ceremony for an investment fund’s construction project. No buildings can be seen for several kilometers in any direction.

-

The local government is attempting to renovate its shantytowns, with limited success.

-

An abandoned construction site on the outskirts of the city. Many such projects have been halted.

In the last two decades, as Longjing’s industrial output has slowed, a wave of workers have gone to South Korea seeking employment. At the outset, most of the men worked as laborers, while the women found jobs as waitresses. Though their adopted country was expensive, the money was good: You could earn tens of thousands of yuan per month in South Korea, while Longjing’s per capita disposable income at the turn of the century was less than 6,000 yuan (then $700) a year.

China’s ethnic Koreans traditionally have large families. Bonds between family members tend to be strong, even where distant relations are concerned. However, as migration to South Korea increased, more and more Chinese Korean women chose to marry men in their adopted country, severing their ties to Longjing’s minority communities.

China and South Korea normalized diplomatic relations in 1992. After this, marriages between Chinese Korean women and South Korean men increased dramatically. By 2004, the divorce rate in Yanbian hit 68 percent. According to South Korean government statistics, in 2016 there were 630,000 Chinese Koreans residing in the country.

In the last few years, as South Korean economic growth has slowed, fewer construction sites have hired male laborers from China. There is still work for the women, however. As Chinese Korean women have gained spending power, more and more of their male counterparts complain that they can’t find women willing to stay in town and run the household.

Wedding decorations still remain in an abandoned hotel.

Most Chinese Koreans who leave Longjing now do so for good. Some save up money earned abroad, return to the city, and open their own businesses — usually restaurants or karaoke bars. As one Han Chinese local, an online shop owner surnamed Li, put it: “In Longjing, you either work for the government, or you run a business out of your house.”

Even in a bad month, Li’s business still earns him around 8,000 yuan — much higher than Longjing’s average wage of about 3,000 yuan a month. But he still worries about the future. “Longjing is as well-connected logistically as Yanbian,” he said. “The main problem is that businesses in the northeast aren’t open as long as in the south of the country. After 2 p.m., delivery companies stop taking orders,” he explained. In the winter months, night falls in Longjing as early as 4 p.m.

Longjing’s commercial street is lined with karaoke bars and stores peddling Korean products. It would not be unusual to walk past a small supermarket and see the employees watching South Korean TV shows. Workers just back from South Korea are their best customers, as they tend to hoard money while abroad and splurge on luxuries when they return, especially during annual festivals.

-

Xu Tongming

“Lots of people leave, but when they come back to visit, they find that they’ve lost their sense of home. I teach taekwondo here.”

-

Ai Ling

“I’m a volleyball player at my university, and I don’t want to leave my hometown.”

-

Li Nan

“I’m a high school student who loves playing the guitar. Korean folk songs are my favorite, but the clothes they wear are too tacky.”

Ai Ling

“I’m a volleyball player at my university, and I don’t want to leave my hometown.”

Xu Tongming

“Lots of people leave, but when they come back to visit, they find that they’ve lost their sense of home. I teach taekwondo here.”

Li Nan

“I’m a high school student who loves playing the guitar. Korean folk songs are my favorite, but the clothes they wear are too tacky.”

North Korea lies on the opposite side of the Tumen River. From the Qing Dynasty onward, Koreans migrated across the Tumen River to settle down in the ancestral lands of the Manchu, despite an imperial edict forbidding them from doing so.

Yanbian’s Korean population was one of the groups hardest-hit by the tumultuous history of early 20th century China. During the Japanese occupation, the imperial army had Koreans help them rule over the Han majority. In the eyes of the Han, Koreans were frequently seen as co-conspirators with the Japanese. After the Communist Party reunified China in 1949, many wealthy Koreans fled to South Korea. During the Korean War, many of those who remained were killed while serving in the Chinese army.

Today, politics on the Korean Peninsula continues to influence the collective mindset of Yanbian’s ethnic minority population. Around a decade ago, China and South Korea arranged a work permit policy whereby ethnic Koreans in China were able to get permission to work in South Korea on request.

-

A hotel on the border with North Korea comes equipped with telescopes that can be used to observe a different way of life to the south.

-

Every winter, local farmers burn straw to replenish their fields with nutrients.

-

Two black bears sit on an elevated platform at a black bear farm.

Most Longjing residents have taken advantage of the policy at some point, but when they return to China, they rarely resettle in Longjing. Instead, they head for the eastern Chinese province of Shandong, where many South Korean companies are based.

When young people finish high school, they now go to bigger cities as well. Walking through Longjing’s streets, you rarely hear the laughter of young children. Before 2000, the city had five primary schools: two for Han Chinese, three for Koreans. Now there are only three, and they count no more than a few thousand pupils between them.

Residents look back fondly on the 1980s and ’90s. During the Cultural Revolution, many university students were sent to farm the countryside around Longjing. Around 18,000 of these young people were from Shanghai, and settled in Longjing during the end of the campaign and the first free-wheeling years of China’s economic reforms. But many returned to Shanghai in the ’90s, when it became apparent that Longjing was slipping inexorably into an economic funk.

The local paper mill, established by the Japanese in 1936, once processed wood pulp into banknotes and high-quality paper products. It even had its own railway tracks and station. After the Second Sino-Japanese War, the mill disposed of its now-invalid banknotes at the behest of the Communist government.

The mill went bankrupt in 1998, and its old workshop is now a glass factory. When I arrived to take photos, the workers shied away from my camera, and a manager came hurrying over. “Don’t photograph them,” he said. “They’re from North Korea.”

Five ethnic Korean children pray in a local church on Sunday.

Since 2005, Longjing’s industrial zone has tried to encourage new businesses and reinvigorate the flagging local economy. Officials hoped that the zone, located just a few bus stops from the city center, would attract investment, develop foreign trade with Russia and North Korea, and swell Longjing’s diminishing population. It didn’t.

There is one area that was supposed to support its economy through trade with Yiwu, a city in eastern China’s Zhejiang province well-known for its small commodities market. But the initiative has seen limited success. Today, the foundations lie exposed, and weeds have overgrown the few dilapidated structures. “This region is too mountainous for trade,” laments Li, the e-commerce merchant. “Logistics costs are too high to get small commodities in and out.”

The industrial zone is 18 square kilometers in size. Construction has gradually dried up, and no businesses are open. Instead, the vast network of roads is used mainly by locals taking their driving tests.